Case Presentation:

You are working in the CCU when you admit a 72-year-old female for shortness of breath. The patient has a past medical history of atrial fibrillation on anticoagulation, HFpEF, HTN, and CKD stage 3a and new chest pain. The patient’s husband notes that the pain started ~1 week ago, but the patient did not present to the ED because she thought it was bad indigestion. Vitals in the ED are temp of 100.2 F, BP 90/70, HR in the 110s, and 85% saturation on room air. The patient is put on a non-rebreather of 40L and is now saturating 97%. On physical exam, the patient appears A&O x 1 (baseline A&O x4) and is in respiratory distress. She is cold and clammy to the touch with rhonchi in the lungs and JVD appreciated just below the patient’s ear.

Labs are notable for high sensitivity troponin 42,844 ng/L (normal <15 ng/L) and NT-pro BNP of 16,573 pg/mL (normal <100 pg/mL). CXR shows bilateral pulmonary congestion concerning for flash pulmonary edema. Bedside echo shows severe mitral regurgitation, which is new for this patient.

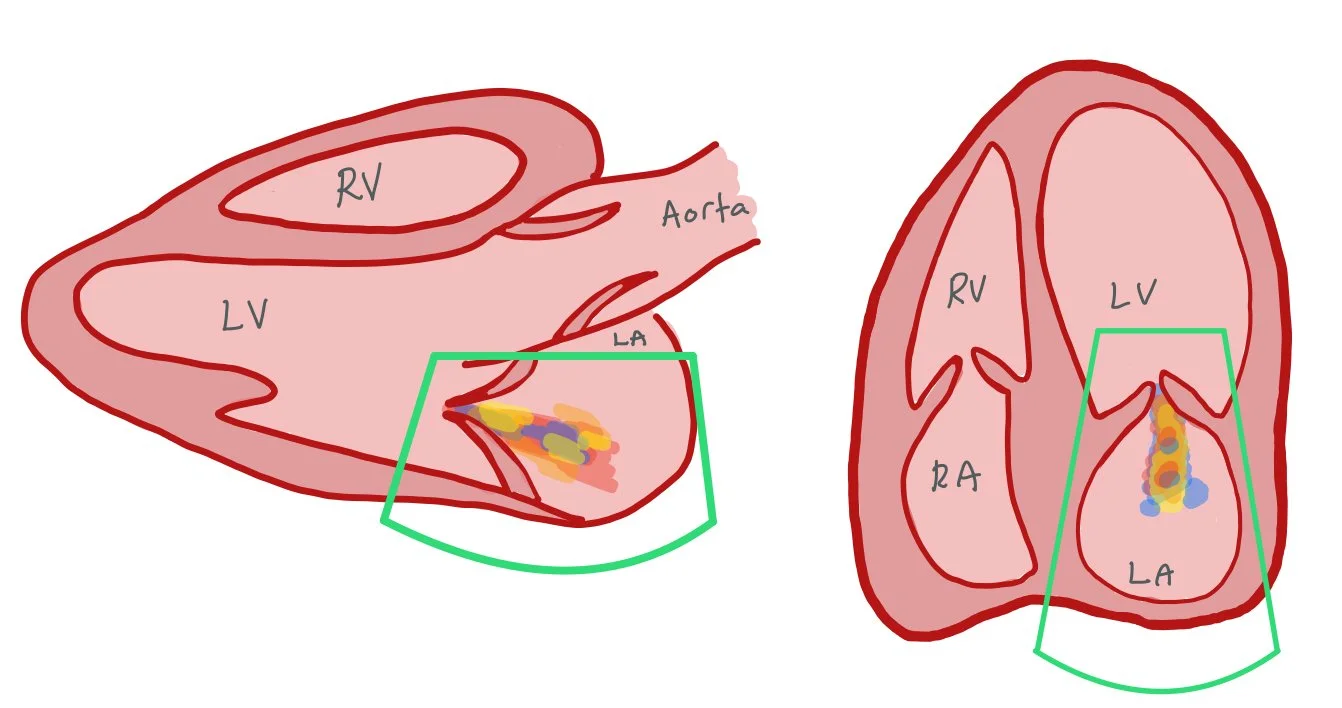

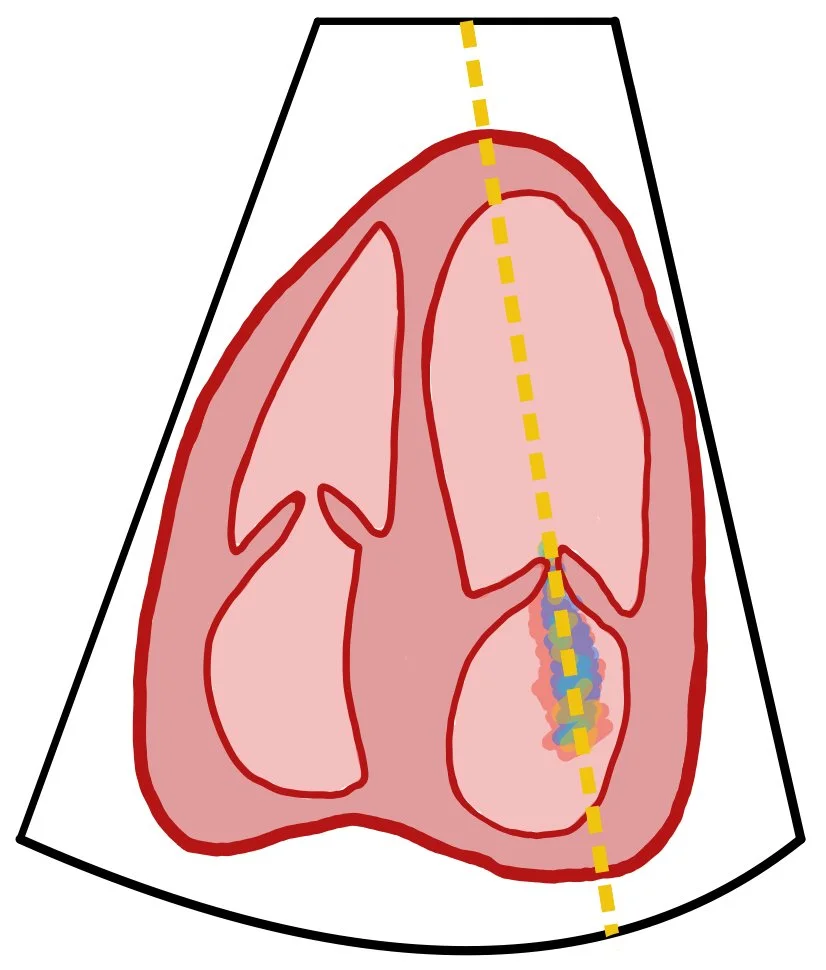

The pictures above show the parasternal long and apical four chamber views of mitral regurgitation (MR). These two views are commonly used to assess for MR. In both pictures, you can see regurgitant blood going from the LV back into the LA.

Ask Yourself:

1. What are some the etiologies of mitral regurgitation (MR), and what are the common TTE findings you will see in patients with MR?

2. In situations with acute MR, how do you diagnose and stabilize these patients?

3. When do you consider intervention for MR? What options do you have?

4. For patients who receive mitral transcatheter edge-to-edge repair (TEER), what are some of the complications? What do you do in the acute setting if patients develop any of these complications?

Background:

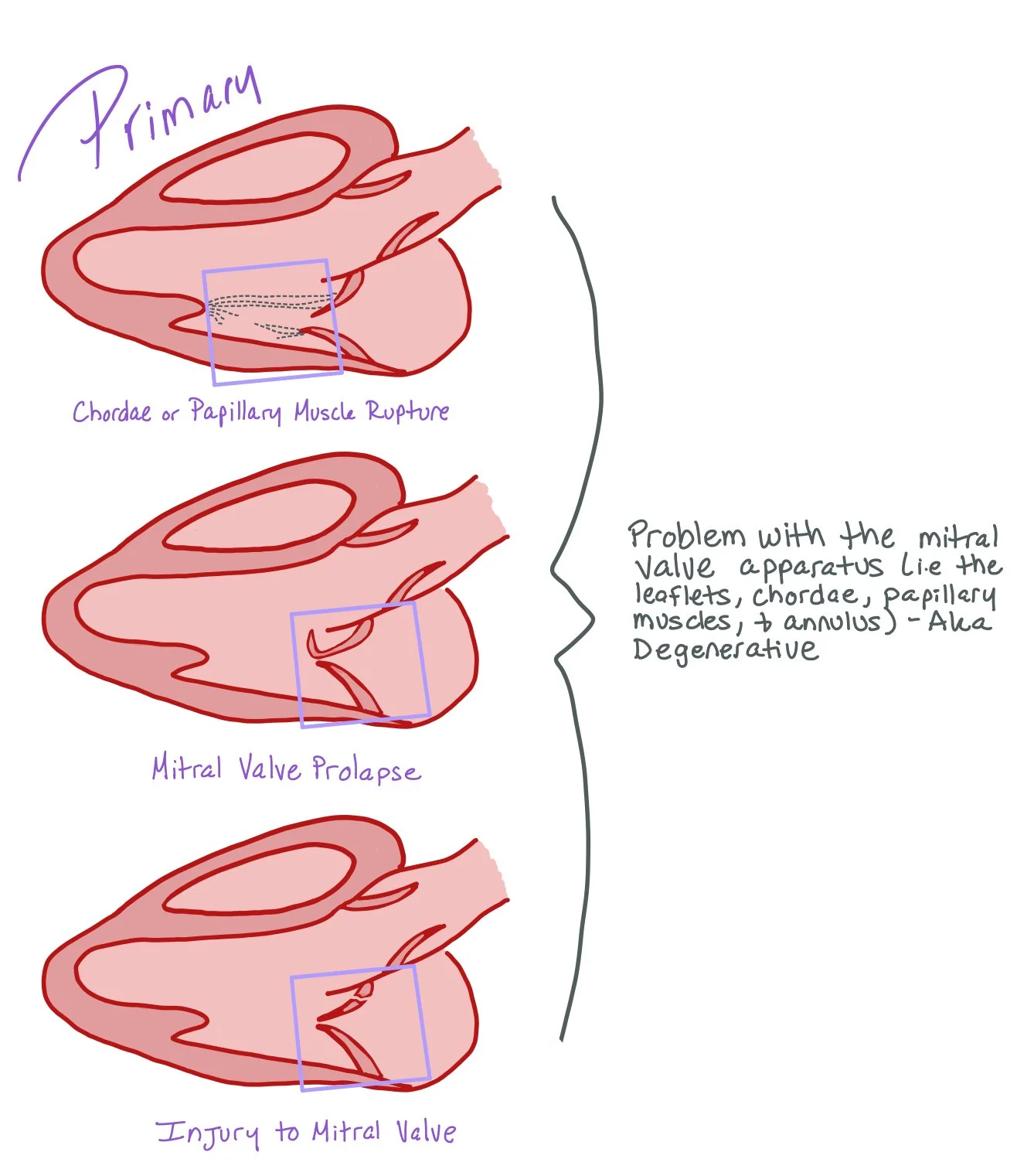

When assessing MR, we need to differentiate whether the MR is due to primary or secondary causes, as well as whether the MR is acute or chronic:

Primary mitral regurgitation is caused by intrinsic structural abnormalities of the mitral valve apparatus itself. In most situations, the leaflets, chordae tendineae, or papillary muscles are affected. Dysfunction of one or more of these structures causes blood to flow back into the left atrium from the left ventricle during systole.

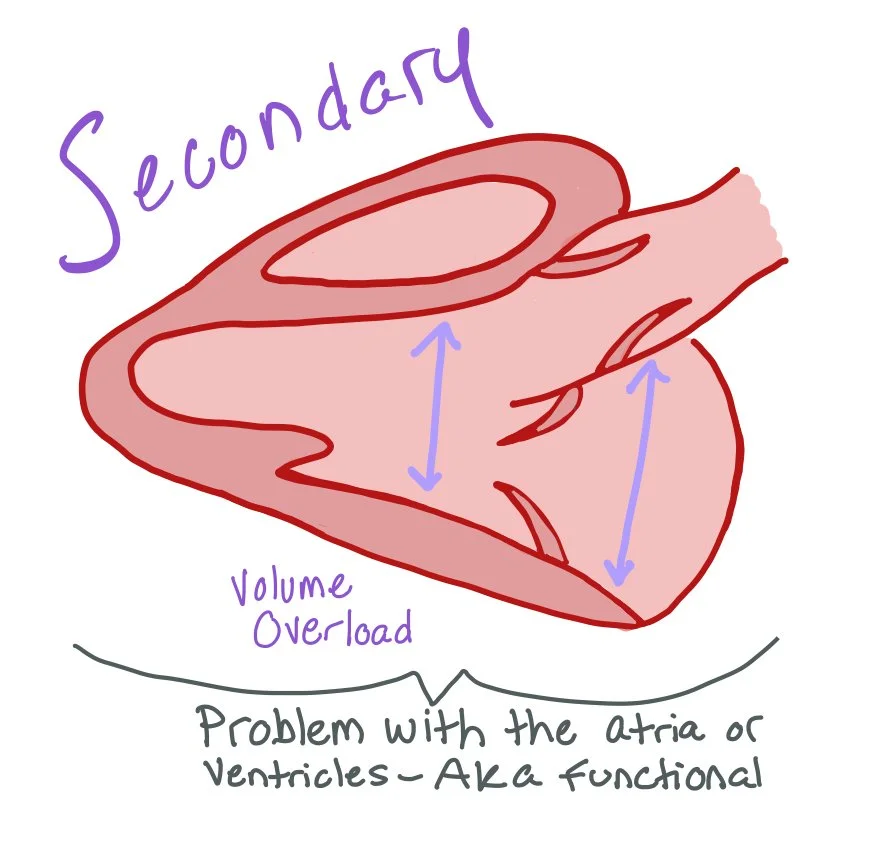

Secondary mitral regurgitation (also called functional MR) occurs when the mitral valve leaflets and chordae are structurally normal, but regurgitation results from geometric or functional changes in the left ventricle (LV) or left atrium (LA).

Primary Mitral Regurgitation Causes:

Mitral valve prolapse (MVP): >2 mm displacement above the mitral annulus. This is seen in more developed countries. Many times, MVP is caused by fibroelastic deficiency disease or myxomatous disease.

Degenerative mitral regurgitation:

Fibroelastic deficiency disease:

Caused by a decrease in connective tissue (collagen, elastin, proteoglycans), causing the leaflets to become thin and translucent. Excessive thinning leads to focal or segmental prolapse and potentially flail due to chordal rupture, commonly localized to a single segment of the posterior leaflet.

Myxomatous disease (also known as Barlow’s valve):

Caused by disruption of the normal structure of the valve and over-accumulation of proteoglycans leading to enlarged, thickened valves. The thickening leads to ballooning of both leaflets into the atrium.

Infective endocarditis (causes leaflet perforation or chordal rupture)

Acute STEMI causing acute papillary muscle rupture

Other: less common forms of degenerative MR, such as connective tissue disorders, including Marfan Syndrome and Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome.

Secondary Primary Mitral Regurgitation Causes:

Chronic volume overload from decompensated heart failure, which causes increased LV size

CAD or idiopathic myocardial disease (non-ischemic) resulting in a dilated LV that causes papillary muscle displacement and leaflet tethering that causes inadequate leaflet coaptation

LV dyssynchrony from bundle branch blocks or RV pacing

Atrial fibrillation or other etiologies that cause increased LA remodeling and dilation, leading to enlargement of the mitral annulus

Picture above courtsey of Yan Topilsky, DOI: 10.3389/fcvm.2020.00084

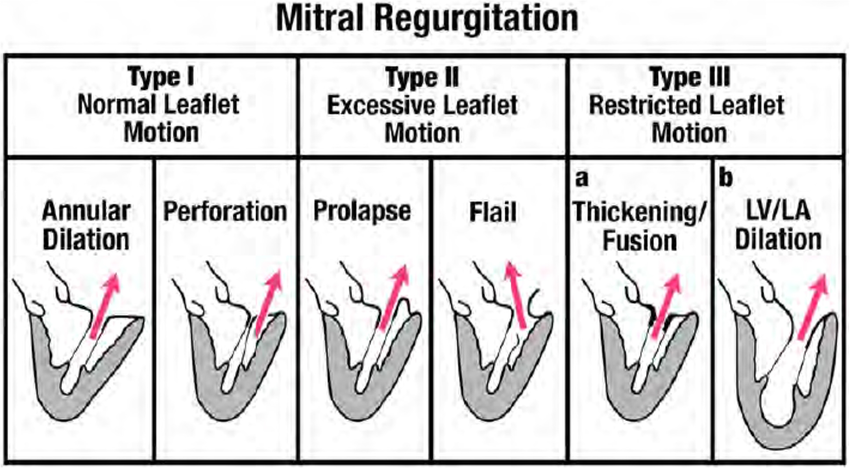

Carpentier Classification:

In addition to determining if the MR is primary vs secondary, another way to classify MR is based on the leaflet motion, aka the Carpentier Classification.

Type 1: Normal leaflet motion with something else causing the MR

Annular dilation (e.g., atrial fibrillation, HFpEF)

Leaflet perforation (endocarditis)

Type 2: Excess leaflet motion that extend beyond the annular plane

Flailed leaflet from chordal rupture

Mitral valve prolapse

Type 3: Restricted leaftlet motion

A: Can be in systole and diastole —> stiff at all times

Rheumatic heart disease

B: Restricted only in systole —> stiff only during systole

Ischemic or dilated cardiomyopathy

Pathophysiology:

Left ventricular preload is increased in both primary and secondary MR due to regurgitant systolic blood flow from the LV to the LA and can cause chronic LV volume overload. Overtime, this may lead to LV and LA dilation and is reflected by symptoms of exertional dyspnea and fatigue due to elevated filling pressures and pulmonary congestion.

Left ventricular afterload is reduced in chronic MR because a portion of the LV stroke volume is ejected backward into the low-pressure LA rather than forward the high-pressure aorta. This reduction in effective afterload allows the LV to appear to maintain a normal or even supranormal ejection fraction early in the disease, despite the presence of significant regurgitation.

Contractility is typically preserved in early primary MR but may decline as the disease progresses and LV remodeling occurs. In secondary MR, contractility is often already impaired due to underlying ischemic or non-ischemic cardiomyopathy, which can be the main driver of MR.

Stroke volume is increased although total LV output (forward plus regurgitant volume), but total cardiac output (forward stroke volume) is usually reduced, especially as LV dysfunction develops. This explains why patients may develop symptoms of low cardiac output despite a normal or high ejection fraction.

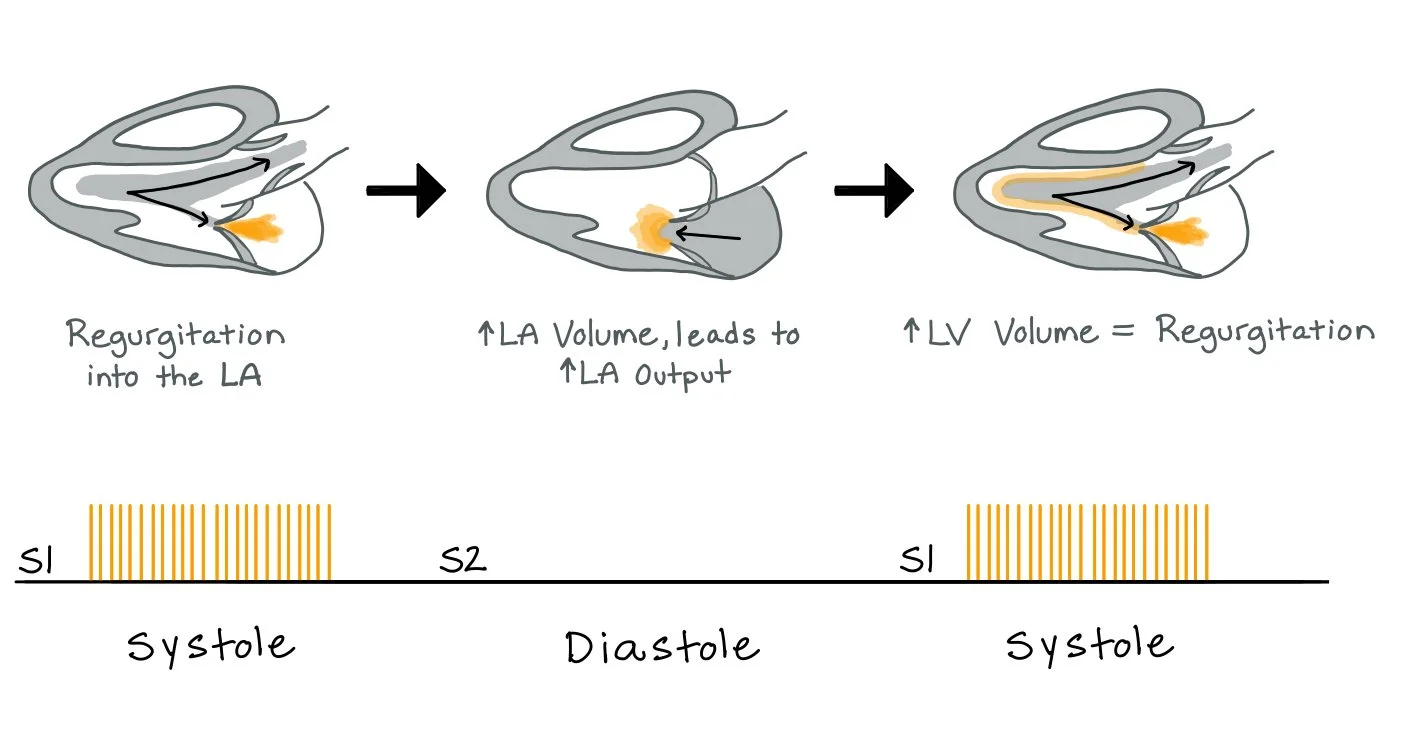

In MR, there is increased regurgitation of blood back into the left atrium (LA). The more regurgitation, the more blood volume in the LA. Over time with significant amounts of regurgitation, the LA may increase in size to accommodate the increase in volume. As a direct result of more volume in the LA, there will be more volume in the LV.

This picture also depicts the holosystolic murmur associated with MR that occurs due to the regurgitation of blood flow into the LA.

Acute Mitral Regurgitation is a rare (incidence 0.05%-0.26%) but devastating (mortality 10-40%) complication secondary to papillary muscle or chordal rupture, leaflet perforation, or infective endocarditis.

In cases of MI, the posteromedial papillary muscle is usually involved as it has a singular blood supply (LCx or the RCA), while the anterolateral papillary muscle is less commonly involved due to dual supply (LAD and the diagonal / marginal branch of the LCx).

On presentation, there may be a holosystolic murmur at the apex radiating to the left axilla classic for MR (which also may be absent due to rapid equalization of LA and LV pressures), pulmonary edema, and cool extremities concerning for cardiogenic shock. The sudden volume overload from the acute valve increases LA and consequently pulmonary venous pressures, leading to pulmonary congestion and hypoxia.

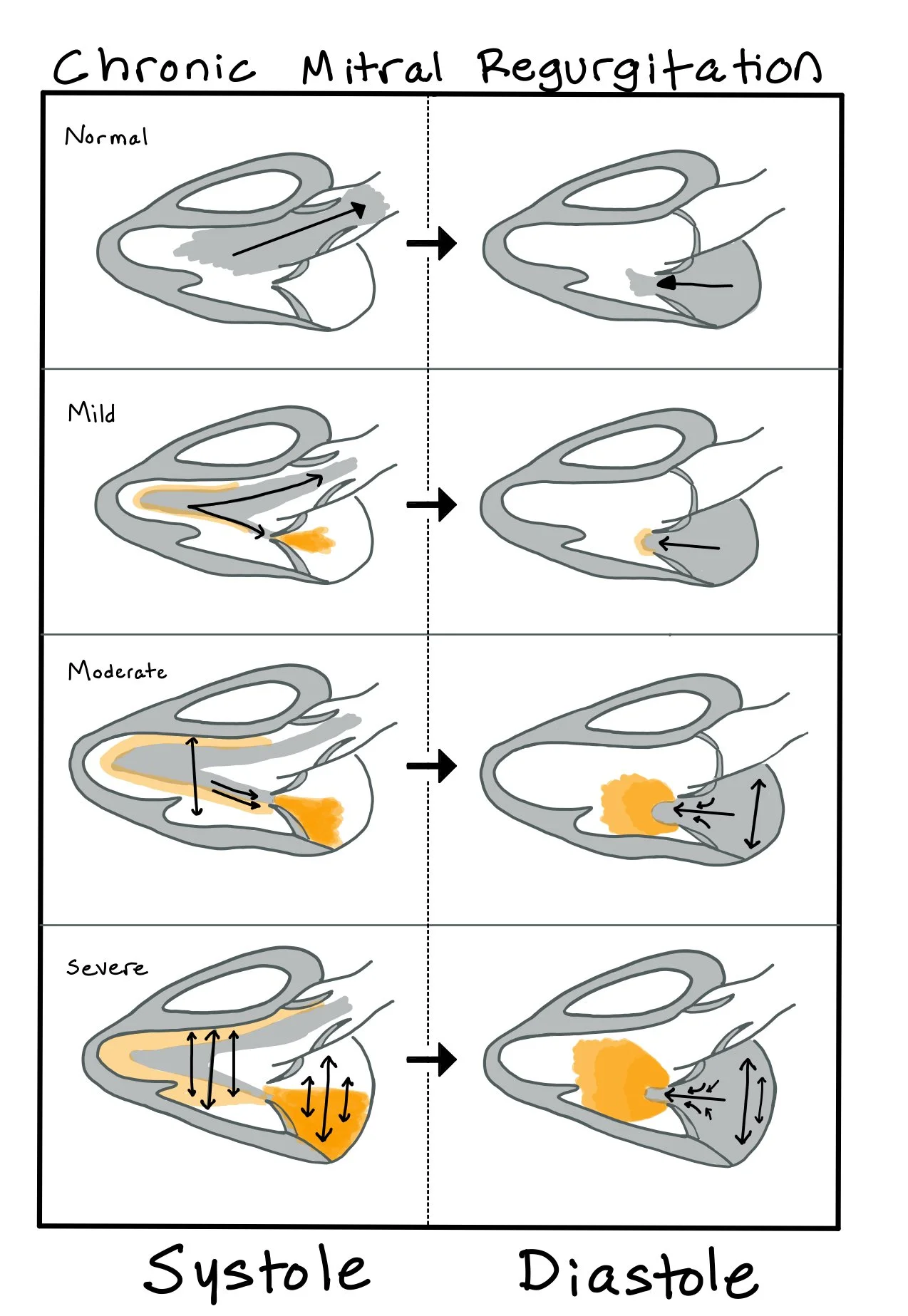

As MR worsens over time, there is LA enlargement due to chronic volume overload.

During systole, regurgitant blood flows from the left ventricle into the left atrium, increasing left atrial volume and pressure. This, in turn, causes an increase in LV and stroke volume.

This picture depicts the changes that occur in the heart as MR progresses from mild to severe.

** Understanding that chronic MR can appear to have normal or increased EF is CRUCIAL to recognize. A normal EF for patients with chronic MR is usually ~70%. This means we have a lower threshold for any decrease in the EF. When the EF decreases to <60%, this is considered LV dysfunction. When the patient’s EF begins to drop to <60% or the LV is so dilated it is unable to contract to <44 mm at end systole, the patient’s mortality increases exponentially as significant LV dysfunction has already occurred.

TTE is the initial modality of choice to help confirm this pathology. Specifically, we want to evaluate:

LV function

RV function

Pulmonary artery pressure

Mechanism of MR

Acute Management:

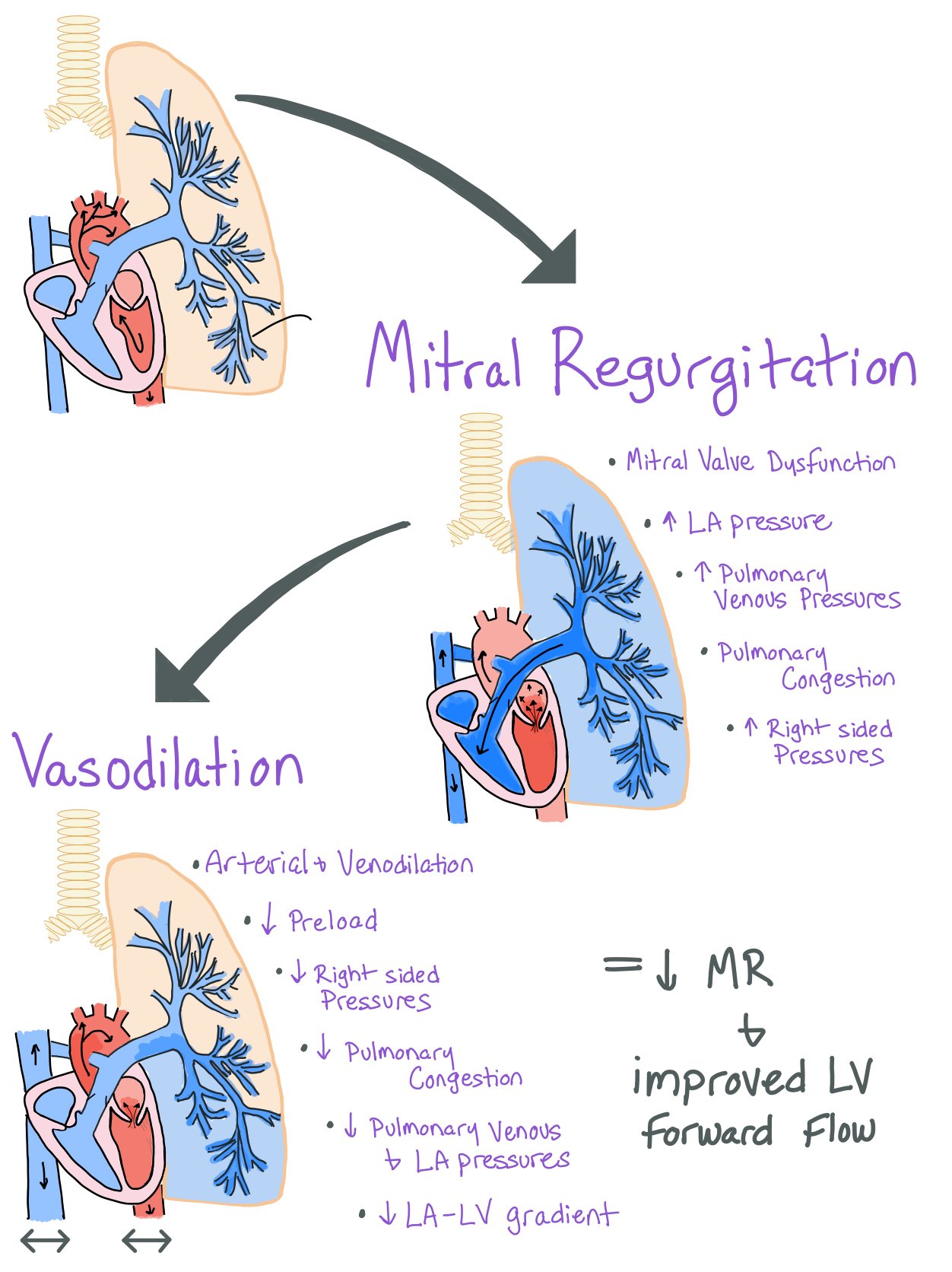

Vasodilatory therapy helps to improve the hemodynamics by reducing:

Preload:

Venodilation reduces the preload and subsequently helps offload the left side of the heart, leading to decreased pulmonary congestion.

Afterload:

Decreased afterload from arterial vasodilation allows for increased forward flow. This occurs due to a reduction in the gradient between the LV and systemic blood pressure, ultimately allowing for an increased LV stroke volume and cardiac output and decreased amount of fluid regurgitating backwards into the pulmonary circulation.

Vasodilatory therapy is contraindicated when systemic vascular resistance is already low, such as with sepsis, cirrhosis, or vasodilatory shock. In these cases, management focuses on supportive therapies for cardiogenic shock – specifically, ensuring the patient has good circulation and oxygen delivery for organ perfusion. This can be achieved with vasopressors, inotropes, or supplemental oxygen / positive pressure ventilation.

Other acute management options include use of mechanical circulatory support devices, such as the intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP). This device functions to help decrease afterload during systole via balloon deflation, thereby increasing forward cardiac output. It also inflates during diastole, helping to increase coronary perfusion pressures and support systemic circulation.

These patients usually require acute mitral valve intervention. In most cases, mitral valve repair is favored over valve replacement.

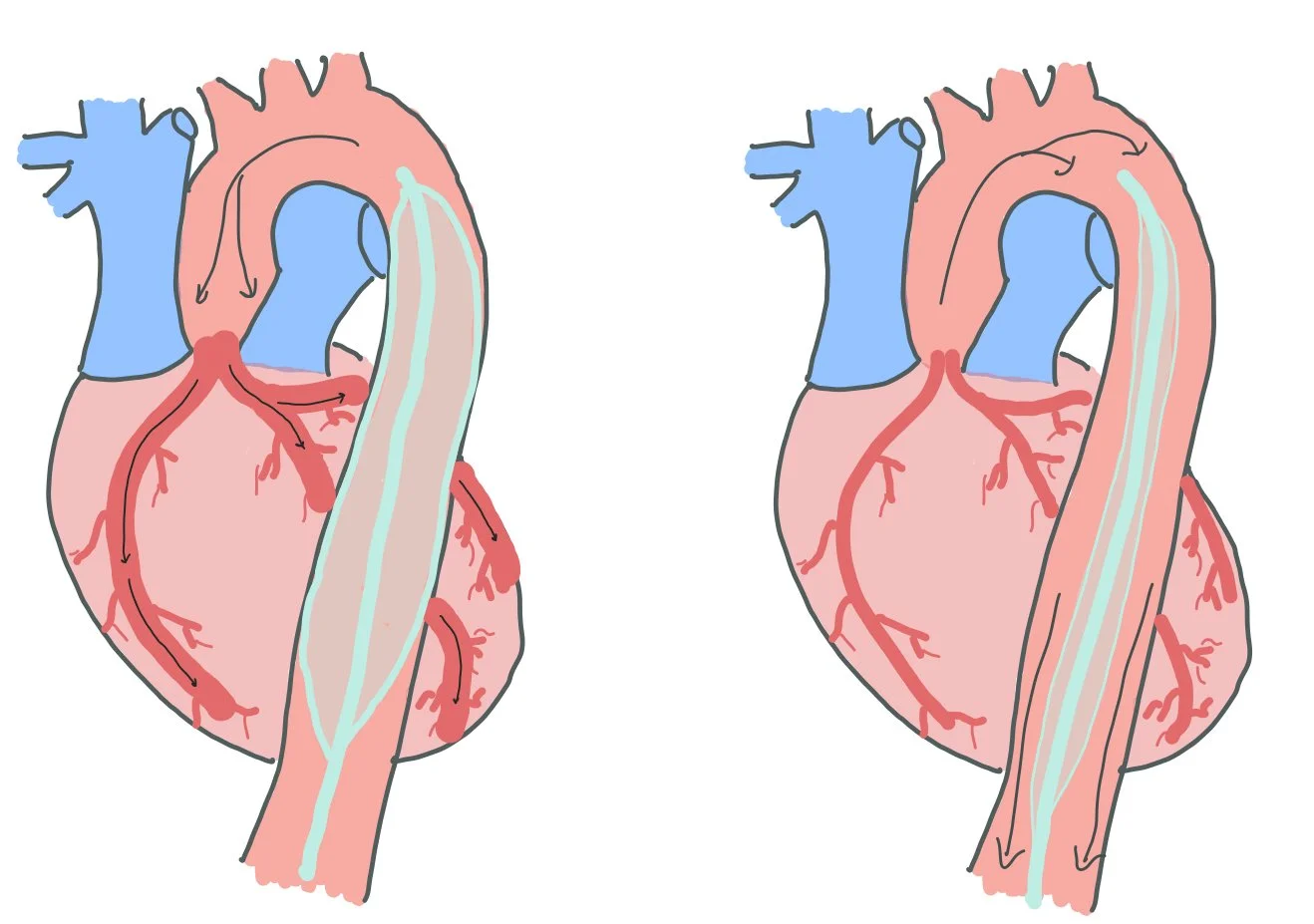

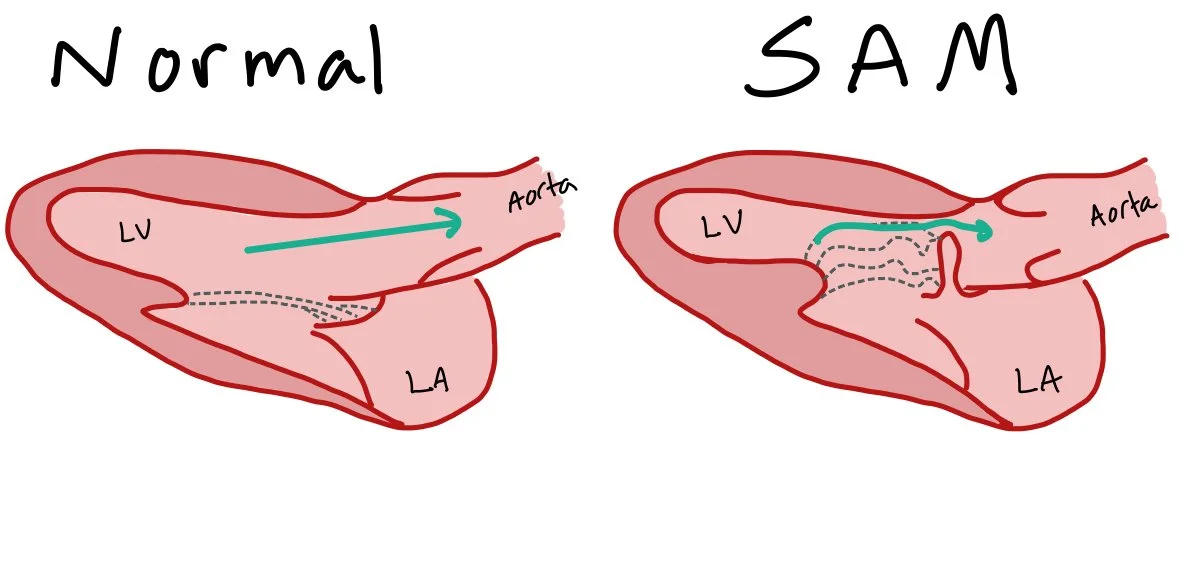

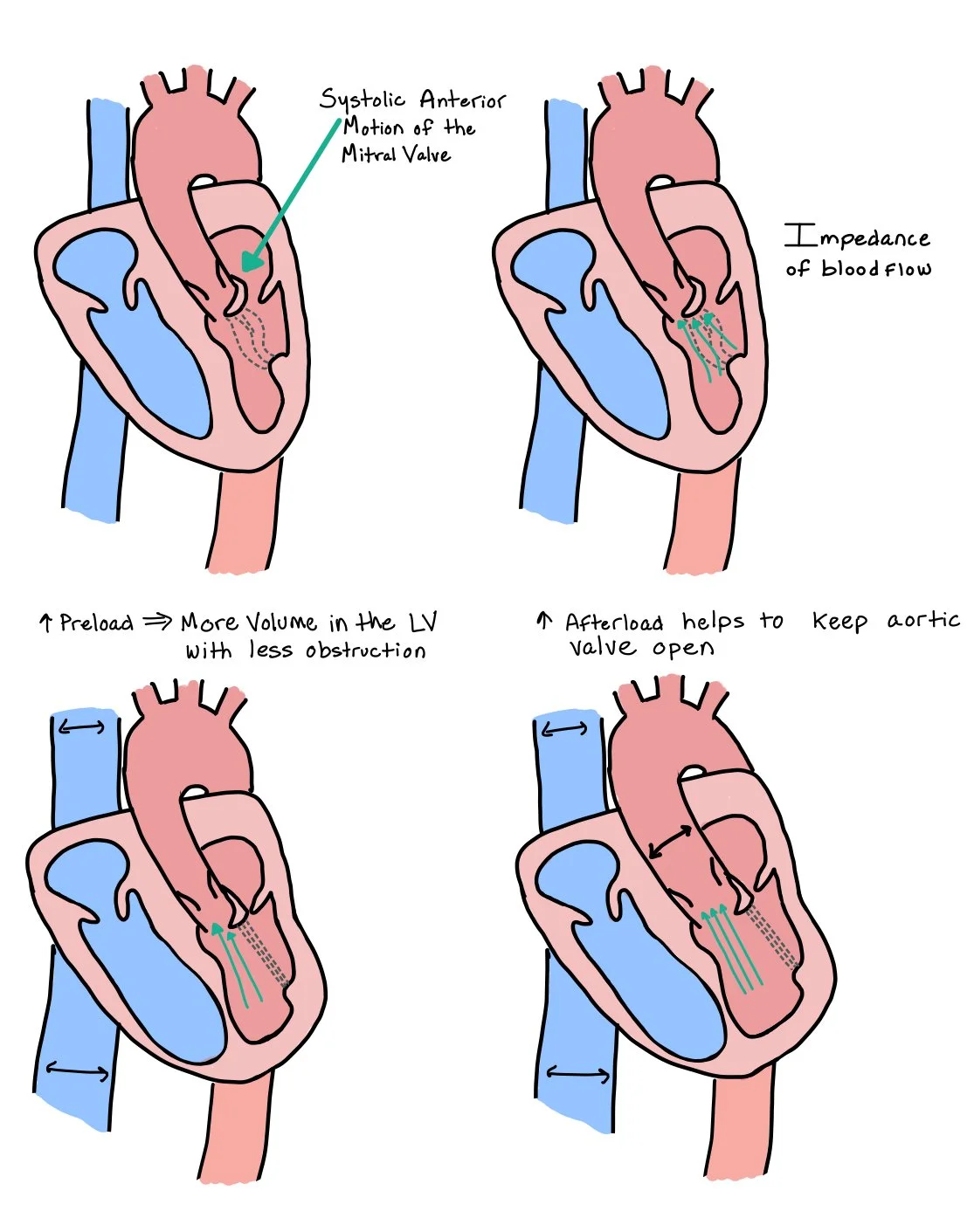

Systolic Anterior Motion of the Mitral Valve (SAM)

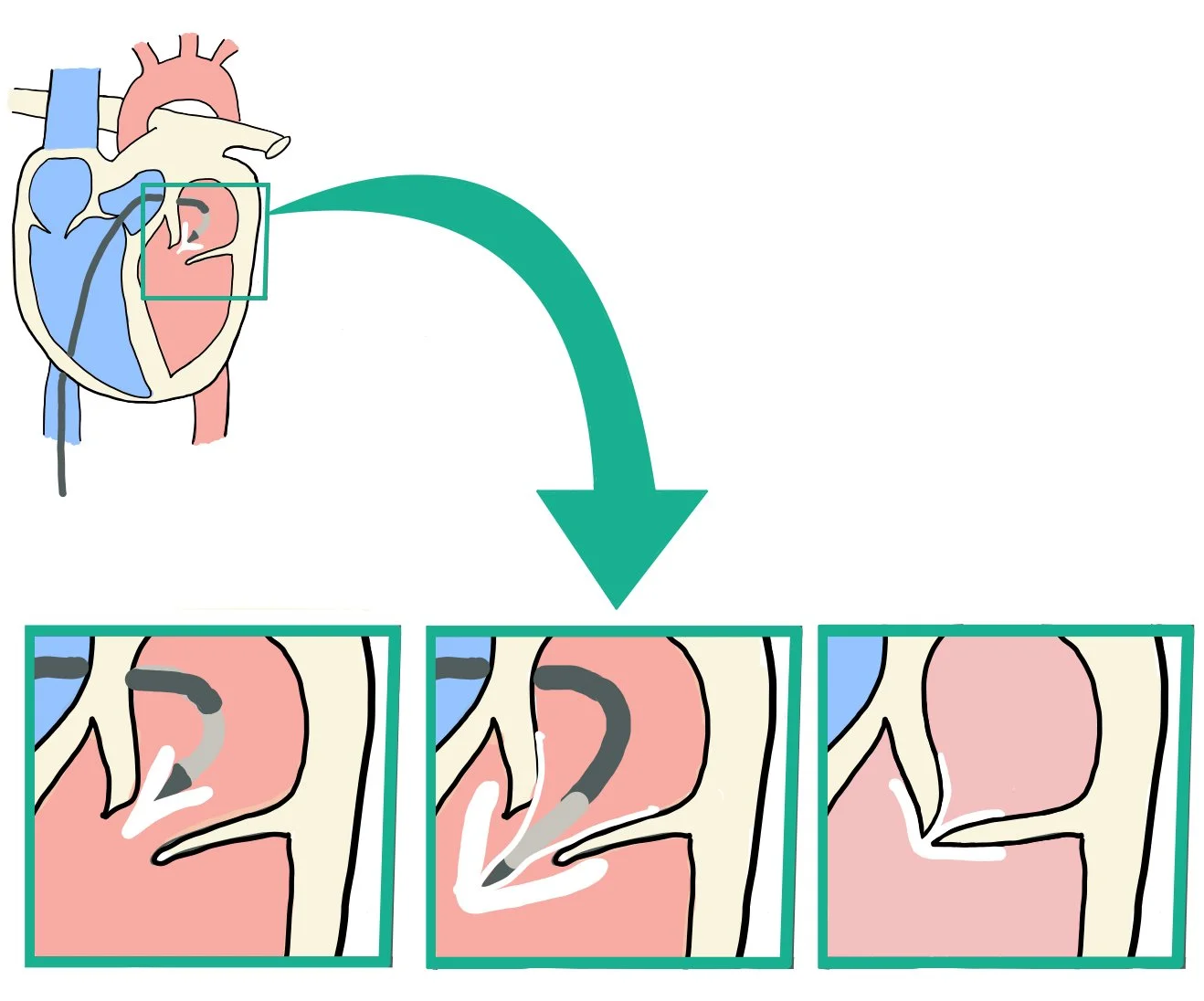

Normally, the aortic valve is open during systole, allowing blood to flow out of the LV into the aorta. When patient’s have SAM, the mitral valve prolapse causes obstruction of through the aorta, as pictured above.

Systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve, aka SAM, is a pathology that occurs when the mitral valve is pulled anteriorly towards the left ventricular outflow track. SAM occurs due to the pull of the mitral leaflet from the high velocity blood exiting the left ventricle.

From a functional standpoint, SAM causes both obstruction of blood flow into the aorta, leading to decreased cardiac output and EF, and mitral regurgitation, causing symptoms of congestion. If the provider is unaware of the SAM pathology, this can initially look like cardiogenic shock and acute decompensated heart failure. SAM is a crucial pathology to recognize as these patients will not respond to typical therapies, such as inotropes, diuresis, or afterload reduction.

On TTE, a left ventricular outflow track obstruction >30 mmHg is usually clinically significant for SAM. You will also see mitral regurgitation. Doppler through the LV outflow tract that shows a “dagger” like appearance.

Causes include:

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

Takotsubo

Distributive shock

Hypovolemia or decrease LV size

Floppy mitral valve leaflets

Tachycardia / increased sympathetic tone

Decreased preload

Decreased afterload

Inotropes

Treatment:

Increased preload: Gives more volume to the LV, which helps to separate the LV walls and decrease mitral valve prolapse.

Increased afterload: The increased pressure from the aorta can improve SAM by helping to keep the mitral valves away from the outflow track due to the increased back pressure.

Workup

Patients with MR most commonly present with exertional dyspnea, fatigue, decreased exercise tolerance, and palpitations. Patients with acute severe MR may present with pulmonary edema or cardiogenic shock, while patients with chronic MR range in presentation from mildly symptomatic to severe shock due to compensation.

Physical exam findings:

On physical examination, a holosystolic murmur at the apex radiating to the axilla is classic for primary MR. Presence of an S3 may indicate severe regurgitation. In secondary MR, the murmur may be softer and less localized. Patients may also have jugular venous distention and other signs of volume overload, such as rhonchi and lower extremity edema.

In acute MR, the murmur may be short and unimpressive during early systole. We may see signs and symptoms of pulmonary congestion due to volume overload from poor forward flow from the LA and LV, especially when the MR is due to acute choral rupture.

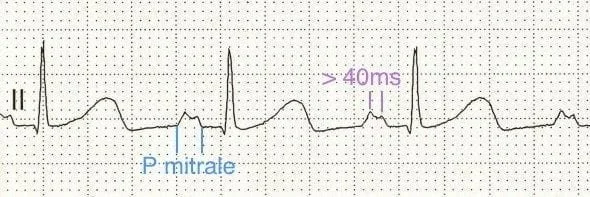

The picture above shows a “P mitrale,” which develops due to atrial enlargement. The picture below shows the different morphologies of P waves that can occur with both left atrial enlargement (LAE) and right atrial enlargement (RAE). Both pictures courtesy of Life In the Fast Lane.

EKG Changes:

Atrial fibrillation:

Since MR causes LA enlargement, the EKG may also show signs of left atrial enlargement, such as with a broad, notched P waves in lead II (pictured). Over time, left atrial enlargement increases the risk for atrial arrhythmias, such as atrial fibrillation.

Left Ventricular Hypertrophy:

These patients can also develop left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) due to the chronic volume overload of the LV, which adapts by eccentric hypertrophy to accommodate the increased preload. There are numerous voltage criteria for diagnosing LVH, but the most common is the Sokolow-Lyon criteria that states the S wave depth in V1 + tallest R wave height in V5 or V6 > 35 mm = LVH. This voltage criteria must be accompanied by non-voltage criteria to be considered diagnostic of LVH, which are increased R wave peak time > 50 ms in leads V5 or V6 as well as ST segment depression and T wave inversion in the left-sided leads.

Ischemia / Bundle Branch Blocks:

In secondary MR, additional ECG findings, such as Q waves and bundle branch block may be seen depending upon the underlying cardiomyopathy or ischemic heart disease. Q waves may indicate prior myocardial infarction, while bundle branch block shows conduction system disease associated with LV remodeling and fibrosis. These findings are more common in secondary MR, where LV dysfunction and remodeling are the main drivers of regurgitation.

Transthoracic Echocardiogram

TTEs are first line when trying to determine if a patient has MR. If we are unable to assess the etiology of the MR or are unsure of the MR severity, the next step would be a TEE to better visualize the valve. Other imaging modalities can help determine severity and etiology of MR, including cardiac MRI and cardiac catheterization.

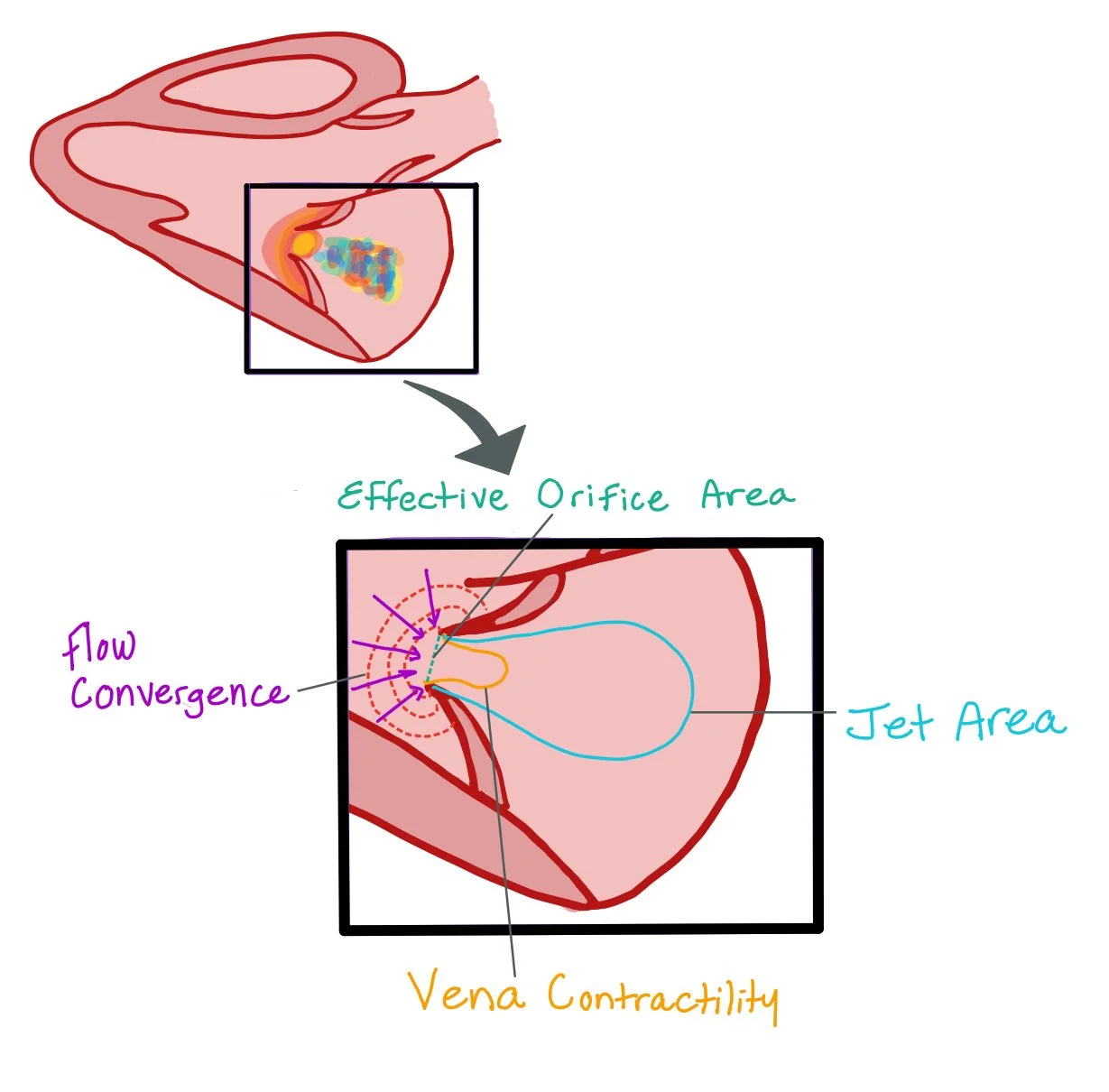

In primary MR, echocardiography reveals leaflet prolapse, flail, or chordal rupture, with compensatory LA and LV dilation in chronic cases. In secondary MR, the leaflets are structurally normal but may show restricted motion, mitral annular dilation, or LV/LA remodeling. Color Doppler demonstrates the regurgitant jet, and quantitative measures (regurgitant volume, effective regurgitant orifice area) assess severity.

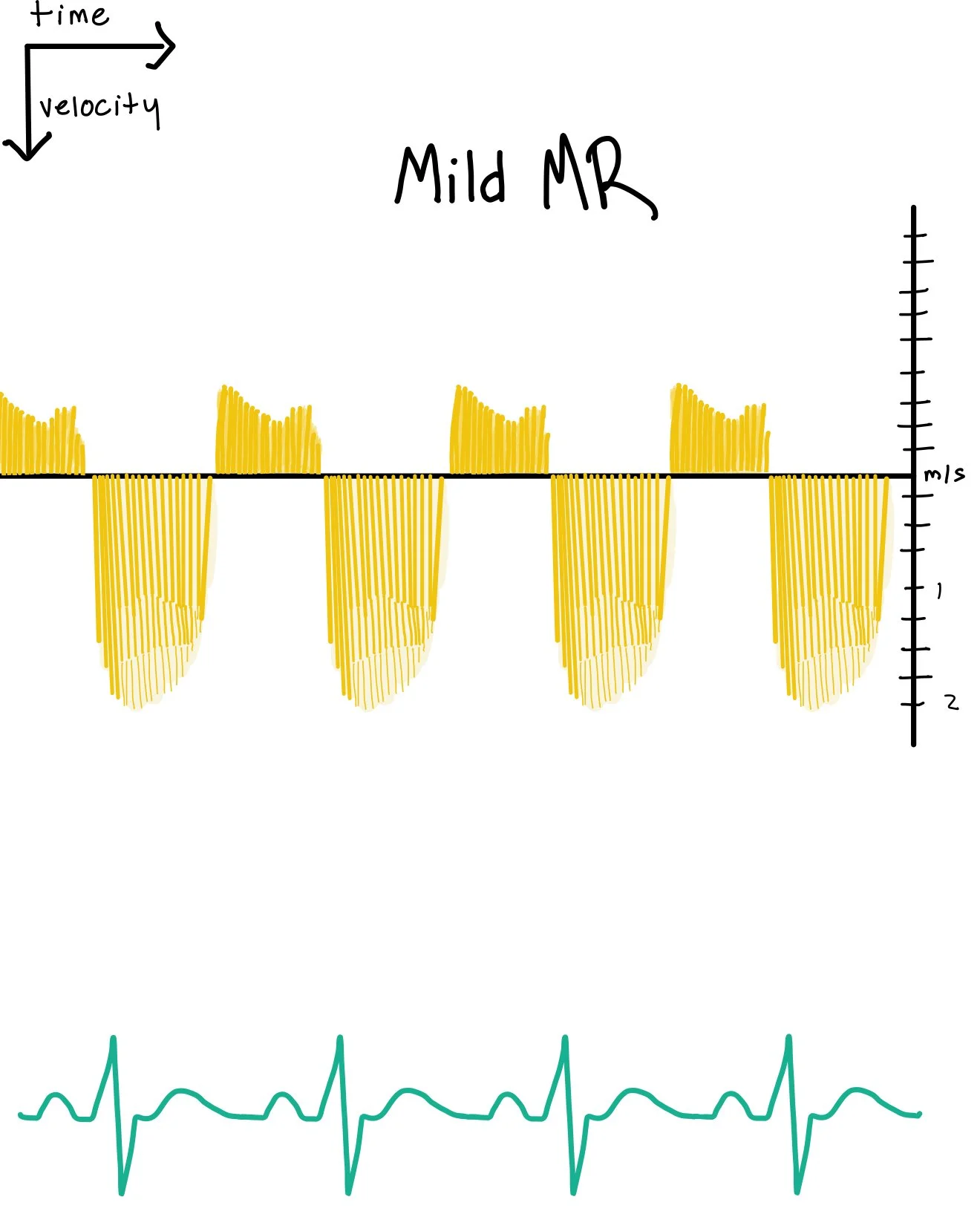

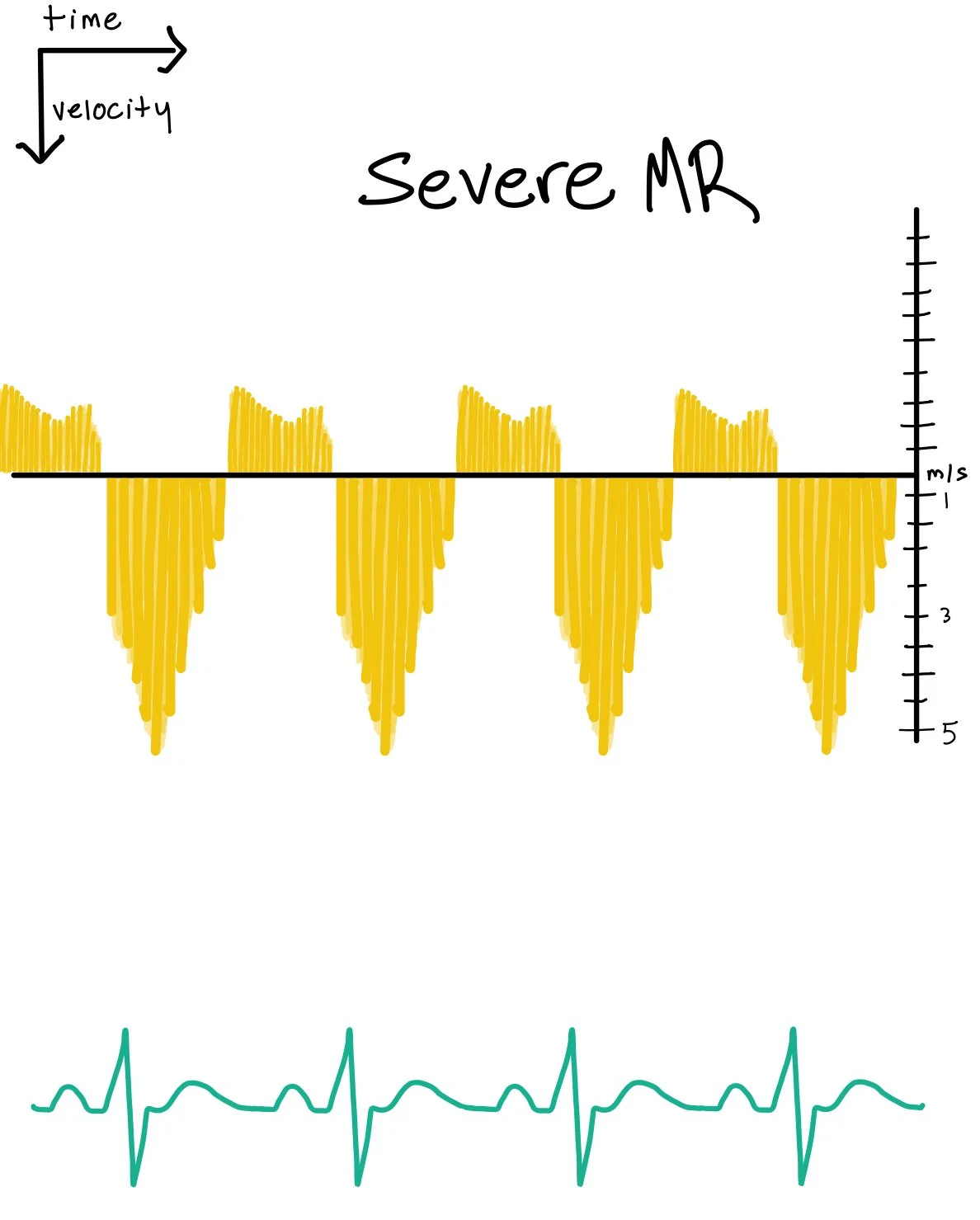

This picture depicts an apical four chamber of a bedside echo with continuous wave doppler through the mitral valve and its regurgitant flow.

CW Doppler measures all velocities along the ultrasound beam, allowing accurate detection of the high-velocity backward flow seen in mitral regurgitation (MR). When you place the CW cursor through the mitral valve, the tracing primarily reflects regurgitant flow from the LV into the LA during systole.

The American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association recommend integrating the following parameters with clinical and other imaging findings to determine MR severity

● EROA (effective regurgitant orifice area) represents the functional size of the regurgitant opening in the mitral valve during systole. It reflects the cross-sectional area through which blood actually regurgitates, not just the anatomical defect.

● Flow convergence refers to the hemispheric region of accelerating blood flow on the ventricular side of the mitral valve as blood is drawn toward the regurgitant orifice. This occurs because streamlines converge as they approach a narrowed opening.

● Jet area is the color Doppler representation of the regurgitant blood flow as it enters the left atrium. It is influenced not only by the severity of regurgitation but also by hemodynamic conditions and left atrial compliance.

● Vena contracta is the narrowest portion of the regurgitant jet immediately distal to the regurgitant orifice. It represents the location where flow velocity is maximal and the jet width is least affected by chamber pressures.

● Regurgitant volume quantifies the absolute amount of blood that regurgitates from the left ventricle into the left atrium per beat.

● Regurgitant fraction expresses the proportion of total LV stroke volume that is regurgitant. Regurgitant Fraction (%) = (Mitral Inflow Volume - Aortic Outflow Volume) / Mitral Inflow Volume x 100

Mild Mitral Regurgitation CW Features:

Lower peak regurgitant velocity variability

Peak velocities are usually normal (often ~4–6 m/s), but the contour is sharp and narrow.

The jet is brief and does not fill all of systole.

“Triangular” or thin signal

The spectral envelope tends to be less dense with incomplete filling.

Reflects a small amount of regurgitant flow.

Shorter systolic duration

The signal may be early or mid-systolic rather than holosystolic.

Physiologic Interpretation:

The regurgitant orifice is small, so less blood volume crosses at high velocity.

The left atrium does not experience markedly elevated early-systolic pressure, so the pressure gradient remains large and velocity stays high but the flow quantity is low.

Severe Mitral Regurgitation CW Features:

Dense, “filled-in” spectral envelope

The tracing is heavily opacified (“complete spectral filling”), indicating large amounts of high-velocity flow.

Holosystolic jet

Regurgitant flow persists through all of systole, reflecting a large, non-terminating leak.

Lower peak velocity with a “blunted” contour

Peak velocity may be lower than expected despite severe MR.

Why? Because the LA pressure rises rapidly, narrowing the systolic LV–LA gradient.

This gives a rounded or blunted peak rather than a sharp spike.

Possible early peaking (deceleration)

If the LA pressure becomes very high early in systole (e.g., acute MR), the CW envelope may become “early-peaking” or triangular, despite large overall volume.

Physiologic Interpretation:

A large regurgitant orifice allows substantial retrograde flow, filling in the Doppler signal.

Rapid equalization of pressure between LV and LA reduces peak velocity; thus lower velocity does NOT mean mild MR—this is a common teaching point.

Stay tuned for the When the Beat Drops: TTE 101 for more information on how to get these measurements!

Indications for Valvular Intervention

When patients have MR, we use staging to help determine when to intervene. The presence of symptoms in patients with severe mitral regurgitation is an indication for intervention, even if the LV function is preserved. When these patients become symptomatic, this signifies that the patient already has changes to the LV or LA, increase in pulmonary artery pressure, decrease in RV function, and / or the coexistence of TR. As such, we intervene regardless of EF. TTE should be done at the time of new symptoms to ensure MR is the cause and rule out other structural pathology. Once these patients have symptoms, mitral valve intervention will help to improve the overall disease course.

Symptoms include exertional dyspnea, orthopnea, or declining exercise intolerance. MR may progress to hepatic congestion, abdominal bloating, and peripheral edema as the increased volume from the left side of the heart causes increased back pressure and venous congestion.

In asymptomatic patients with severe MR, a TTEs should be done every 6-12 months to monitor the progression of the MR and pulmonary artery systolic pressures (PASP). TTE should also be ordered with any onset of symptom (including the onset of atrial fibrillation) to assess the structural changes and LV function.

Patients with severe MR who develop atrial fibrillation should have their valves repaired!

Severe MR and symptomatic? FIX!!!

** The longer severe MR is delayed, the higher the mortality. Therefore, it is crucial that we carefully monitor for any change in the LV function and pulmonary artery pressures so we can intervene early. The biggest goal in asymptomatic MR is to correct the valve issue prior to the onset of LV dysfunction

When there are discrepancies between imaging and symptoms (i.e. the imaging looks like severe MR but the patient is asymptomatic or vice versa), coronary catheterization can be used to help assess for elevated filling pressures. Generally speaking, the higher the filling pressures, the worse the MR. LV ventriculography can also be used to assess the flow of blood from the LV to the LA, helping to determine MR severity. Exercise stress echo can also be used to assess for symptoms and true functional capacity.

Severe MR and ASYMPTOMATIC? Use the 4-5-6 Rule:

4- LV end-systolic diameter > 4cm

5- PASP > 50 mmHg

6- LV EF <60%

GDMT remains the cornerstone for medical management in patients with LV dysfunction from severe MR. GDMT improves symptoms and improves survival in this patient population, and helps reduce LV volumes and reduce severity of MR. In patients who remain symptomatic despite maximally tolerated GDMT, transcatheter intervention can be considered as a 2a recommendation (LVEF 20-50%), as demonstrated in the COAPT trial. GDMT should also be used in patients who are not candidates for valvular interventions.

Note that there is no indication for routine vasodilatory therapy in patients with chronic MR, although blood pressure control remains important. Patients with chronic severe secondary MR and heart failure with reduced EF should always be managed by a cardiologist.

Repair vs. Replacement

Determining the path of intervention depends on the etiology and acuity of the MR. In cases where mitral valve intervention is required, guidelines usually recommend valve repair instead of valve replacement as repair usually leads to fewer cases of patients requiring repeat intervention. However, if the patient requires a complex repair and is young, they may be better candidates for mitral valve replacement with a mechanical valve as the replaced valve may be more durable than a repaired valve.

Percutaneous intervention with mitral transcatheter edge-to-edge repair (M-TEER) is pictured here. M-TEER is selected for mitral regurgitation when a patient is at high or prohibitive surgical risk, has suitable mitral valve anatomy, and has persistent symptoms despite optimal guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) in functional (secondary) MR.

During this procedure, TEE is used to rule out left atrial appendage thrombus as the catheter is often directed toward this area before it turns to cross the mitral valve. We also make sure to get a gastric view of the valve to trace the valve area by planimetry to ensure that there is no mitral stenosis at the start of the procedure. Doing this also allows us to ensure that the clip itself does not cause mitral stenosis.

Mitral valve repair offers the advantage of preserving the patient’s native valve apparatus, which contributes to superior long-term outcomes compared to replacement. The native valve, supported by its chordae tendineae, helps maintain left ventricular geometry and function, an important factor that prosthetic valves cannot replicate. Valve repair is associated with greater durability than even mechanical replacements, and, while the repair itself is typically long-lasting, recurrent mitral regurgitation (MR) can occur due to progression of the underlying disease rather than failure of the repair. Additional benefits include a lower risk of prosthetic valve endocarditis and avoidance of long-term anticoagulation.

The procedural risk of mitral valve repair is low, with less than a 1% chance of major adverse events, including mortality. Outcomes are comparable between open sternotomy and minimally invasive approaches, such as robotic-assisted or right thoracotomy (keyhole) techniques. Minimally invasive repair is associated with reduced tissue trauma, lower postoperative atrial fibrillation risk, decreased need for blood transfusion, shorter hospital stays, and faster recovery. A full sternotomy may still be indicated in cases requiring concomitant coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), in the presence of extensive aortoiliac atherosclerosis, or with significant chest wall abnormalities such as pectus excavatum.

The only time replacement is preferred over repair is with rheumatic heart disease, due to high occurrence of stenosis or regurgitation at 10 years s/p repair that usually occurs due to thickened/calcified leaflets or sub-valvular disease with chordal fusion or shortening.

In secondary MR, treatment typically prioritizes management of the underlying ventricular dysfunction, with the need for valve intervention determined after assessing ventricular response.

Complications…

Different complications can arise for mitral valve procedures, and they depend on the type of procedure the patient receives. There are also different sets of complications for the different surgical approaches, whether it is the minimally invasive laparoscopic approach or the sternotomy.

TEER Complications

Thromboembolic Events

Catheters/devices in the LA increase thrombosis risk during transeptal access.

Prevent with adequate intraprocedural anticoagulation.

Major cardiac/cerebrovascular events: 3–7%; inpatient MI/stroke: 0–3%.

Persistent Atrial Septal Defect (ASD)

Iatrogenic ASD persists in 40–50% of patients.

Unclear clinical significance; monitor with 3D TEE.

Access Site Complications

Right femoral venous access (24F) can lead to pseudoaneurysm, AV fistula, hematoma, retroperitoneal bleed, thrombosis, infection, or vessel injury.

Consider imaging in hypotension or post-procedure Hgb drop.

Serious access events: 1.4–4%.

Device Complications

a. FunctionalDevice failure causing obstruction or persistent/worsened MR.

Persistent MR drives prognosis and need for reintervention; assess with 3D TEE.

Acute MS (<1%), more common in primary MR; mean gradient >5 mmHg linked to adverse outcomes.

b. Structural

SLDA (0–4.8%): most common structural issue; usually acute and managed with additional clip. Subacute/late cases relate to poor tissue quality. Prevent with high-quality 3D TEE imaging.

Clip embolization (<1%): loss of both leaflet attachments; requires urgent surgical retrieval.

Surgical Complications

Bleeding

More common with open surgery due to invasiveness and bypass.

Minimize with meticulous technique and individualized perioperative anticoagulation.

Atrial Fibrillation

New-onset AF is more frequent post-surgery due to atrial manipulation.

Prevention: beta-blockers, prophylactic amiodarone in high-risk patients, and early rhythm/rate control.

Prosthesis-Related Issues

Includes valve thrombosis, structural deterioration, endocarditis, and repair failure/SAM.

Reduced with careful patient selection, detailed imaging, and experienced surgical centers.

Back to the Case:

1. What are some the etiologies of mitral regurgitation (MR), and what are some common TTE findings you will see in patients with MR?

When determining the cause of mitral regurgitation, it’s important to differentiate between primary vs. secondary etiologies. Primary mitral regurgitation is caused by intrinsic structural abnormalities of the mitral valve apparatus itself (such as from MI, endocarditis, mitral valve prolapse, etc). In contrast, secondary mitral regurgitation (also called functional MR) occurs when the mitral valve leaflets and chordae are structurally normal, but regurgitation results from geometric or functional changes in the LV or LA (such as volume overload from heart failure).

When getting a bedside TTE, you may see regurgitation into the LA with color doppler on the parasternal long, parasternal short, and apical images. Many times, this can cause increased left atrial size, elevated pulmonary pressures, and pulmonary regurgitation. In cases of MI, you may see wall motion abnormalities. In many instances, the mitral regurgitation jet will point opposite the valve abnormality (i.e. if the anterior mitral leaflet is involved, the jet will point posteriorly). The main exception to this is with posteromedial MIs that cause papillary muscle rupture, where the jet will be pointed posteriorly although the problem is with the posterior valve.

2. In situations with acute MR, how do you diagnose and stabilize these patients?

TTE is always the first line for diagnosing MR! The main issue with acute MR is the acute volume overload in the LA and LV. Vasodilatory therapy helps to improve the hemodynamics by helping to offload the left side of the heart, allowing for less pulmonary congestion and helping to increase cardiac output.

In the case of acute hemodynamic compromise, intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) may be helpful by helping to lower the systolic aortic pressure, decreasing the LV afterload, and increasing forward output. The IABP may also help increase the diastolic pressures and MAP, which helps to support the systemic circulation.

These patients usually require acute mitral valve surgery. In most cases, mitral valve repair is favored over surgical repair.

3. When do you consider intervention for MR? What options do you have?

Indications for repair are based on acuity and etiology. Acute severe primary MR usually require valve surgery. Intervention may be recommended in asymptomatic chronic MR depending on LV function. Chronic symptomatic severe MR is an indication for intervention. Surgical repair is favored over replacement. Transcatheter options are only for patients who aren’t surgical candidates.

4. For patients who receive mitral transcatheter edge-to-edge repair (TEER), what are some of the complications? What do you do in the acute setting if patients develop any of these complications?

Complications of TEER include thromboembolic events, persistent atrial septal defects, access site complications, device issues (such as the device malfunctioning, persistent MR, and acute MR). If the patient is hemodynamically unstable, call the structural cardiologist who placed the device and CT surgery. Doing a bedside POCUS can be helpful in determining the complication. These patients may require mechanical support, repeat transcatheter repair, or surgery, depending on the severity of the complications.

Further Learning:

Resident Responsibilities

If you are concerned with acute MR, try to get a bedside POCUS STAT!

Acute MR may be due to ischemia!! Make sure to rule this out!

When patients with primary MR start to become symptomatic (i.e. dyspnea on exertion, orthopnea, etc), this is an indication for repair

Remember the 4-5-6 rule! Patients with severe MR who are asymptomatic but develop LV dilation <4cm, PASP >50 mmHg, or EF <60%, must get their valve replaced!!

Further Learning:

Internet Book of Critical Care: LVOT obstruction

Cardionerds: Mitral Regurgitation and podcast by Dr. Rich Nishmura

How’d we do?

The following individuals contributed to this topic: Pranayvir Lotey; Cali Clark, DO MBA; Clay Hoster, MD

Chapter Resources:

Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2021;143(5):e72-e227. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000923

Douedi S, Douedi H. Mitral Regurgitation. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; Updated April 30, 2024. Accessed December 11, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553135/

Asgar AW, Mack MJ, Stone GW. Secondary mitral regurgitation in heart failure: pathophysiology, prognosis, and therapeutic considerations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015 Mar 31;65(12):1231-1248.

Antonakaki D, Moscatelli S. How to assess mitral valve prolapse and mitral annular disjunction, how to look for arrhythmogenic features. Cardiovascular Genomics Insight, Volume 7. European Society of Cardiology; 2023. Accessed December 11, 2025. https://www.escardio.org/Councils/Council-on-Cardiovascular-Genomics/Cardiovascular-Genomics-Insight/Volume-7/how-to-assess-mitral-valve-prolapse-and-mitral-annular-disjunction-how-to-look

van Wijngaarden AL, Kruithof BPT, Vinella T, Barge-Schaapveld DQCM, Ajmone Marsan N. Characterization of degenerative mitral valve disease: differences between fibroelastic deficiency and Barlow’s disease. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2021;8(2):23. Published February 22, 2021. Accessed December 11, 2025. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7926852/