Case Presentation:

You are working in the CCU when a 55-year-old male with a PMH of HTN, tobacco use, and family history of premature CAD presents for acute chest pain found to have acute coronary syndrome. He is taken to the cath lab where he is found to have a full occlusion of the left anterior descending artery (LAD). He is now s/p PCI and stent placement. He’s concerned about his health, especially his cholesterol levels, as his father had a heart attack at a young age. Before his MI, he notes that he felt more tired lately and is aware that he needs to lose weight and exercise more, though his blood pressure is under control with medication. He is feeling better and wants to know what medications he will be leaving with to help improve his cardiovascular health and risk factors.

Vital Signs:

BP 128/78, HR 72 bpm, RR 16, T 98.2 °F

Laboratory Results:

Total Cholesterol: 235 mg/dL

Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol (LDL-c): 159 mg/dL

High-Density Lipoprotein Cholestero (HDL-c)l: 40 mg/dL

Triglycerides: 180 mg/dL

HbA1c: 6.4% (normal)

Creatinine: 1.1 mg/dL (normal)

Social History:

Smokes 1 pack per day (ppd) for the past 30 years. Wants to quit.

Occasionally consumes alcohol (3-4 drinks per week)

Sedentary lifestyle

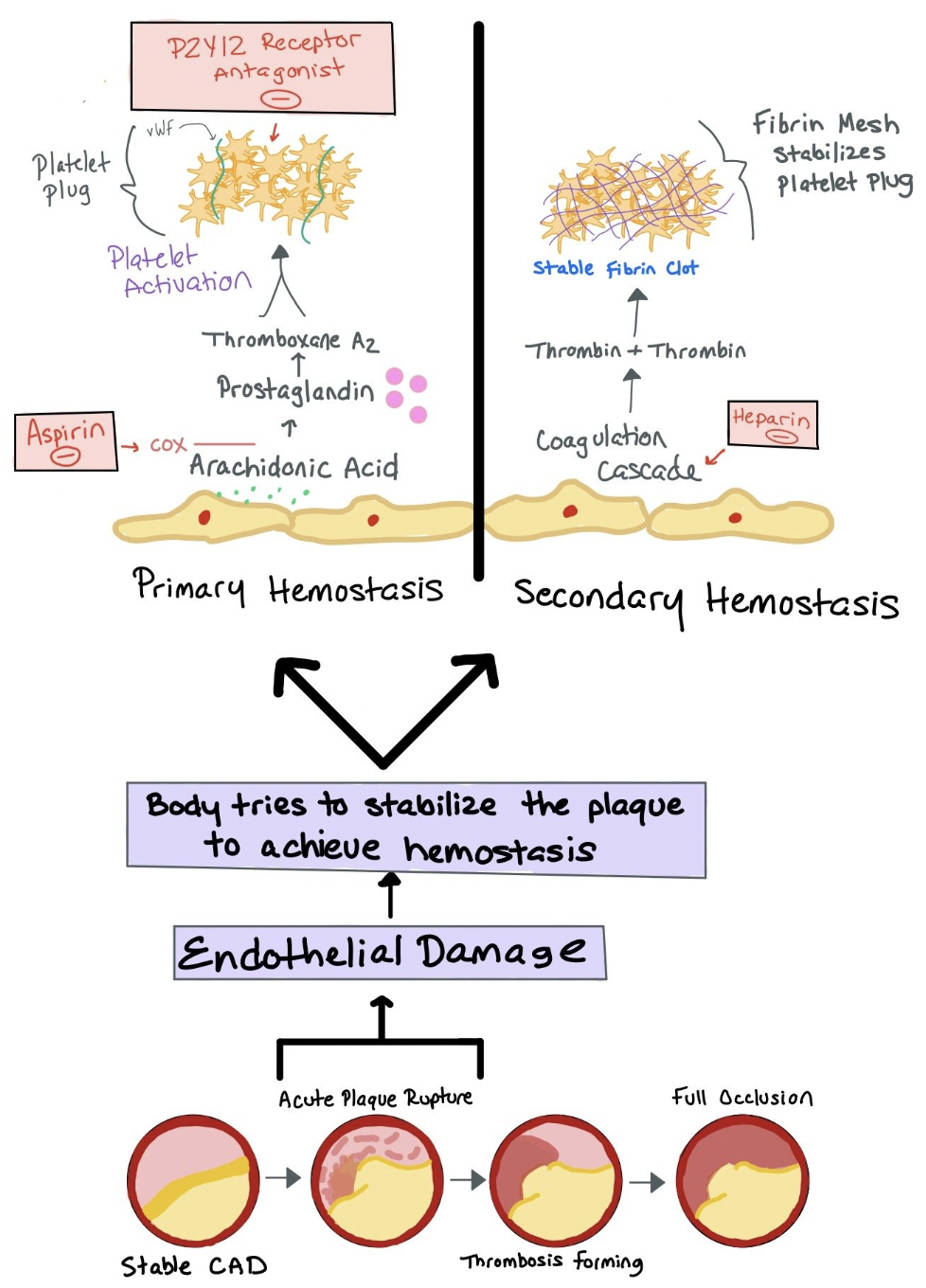

Picture depicting plaque build-up that can lead to acute plaque rupture. The body then tries to stabilize the plaque by both primary and secondary hemostasis.

Ask Yourself:

When thinking about lipid management, what considerations do you need to have? What resources should you be using when determining which therapies a patient should be treated with? What is a coronary CT scan and when should you consider getting this scan to help establish cardiovascular risk?

Which medications or drug classes would you first consider initiating in this patient? How frequently should you be checking lipids? If you need to escalate or change the medication due to ineffectiveness or adverse drug reactions, which medications should you consider adding?

Does it matter if a patient was fasting prior to getting the lipid panel? If so, why does it matter? Can you use any information from that lab test? What if you also got a Lipoprotein (a) test?

If a patient has high triglycerides, should you treat them?

What is the role of aspirin in primary prevention of cardiovascular disease? When should we consider or discontinue this medication in our patients?

Background:

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States. Lowering low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-c) can reduce the risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in patients without a diagnosis of CVD (primary prevention) or decrease the risk of recurrent disease (secondary prevention). While prevention strategies occur at the population level but must also engage individual patients.

When determining our patient’s risk for CVD, we put a lot of emphasis on the patient’s cholesterol levels as buildup of atherosclerotic plaque increases risk for acute plaque rupture (i.e. acute coronary syndrome). Here are a few lab tests we order to help determine risk:

Lipid panel:

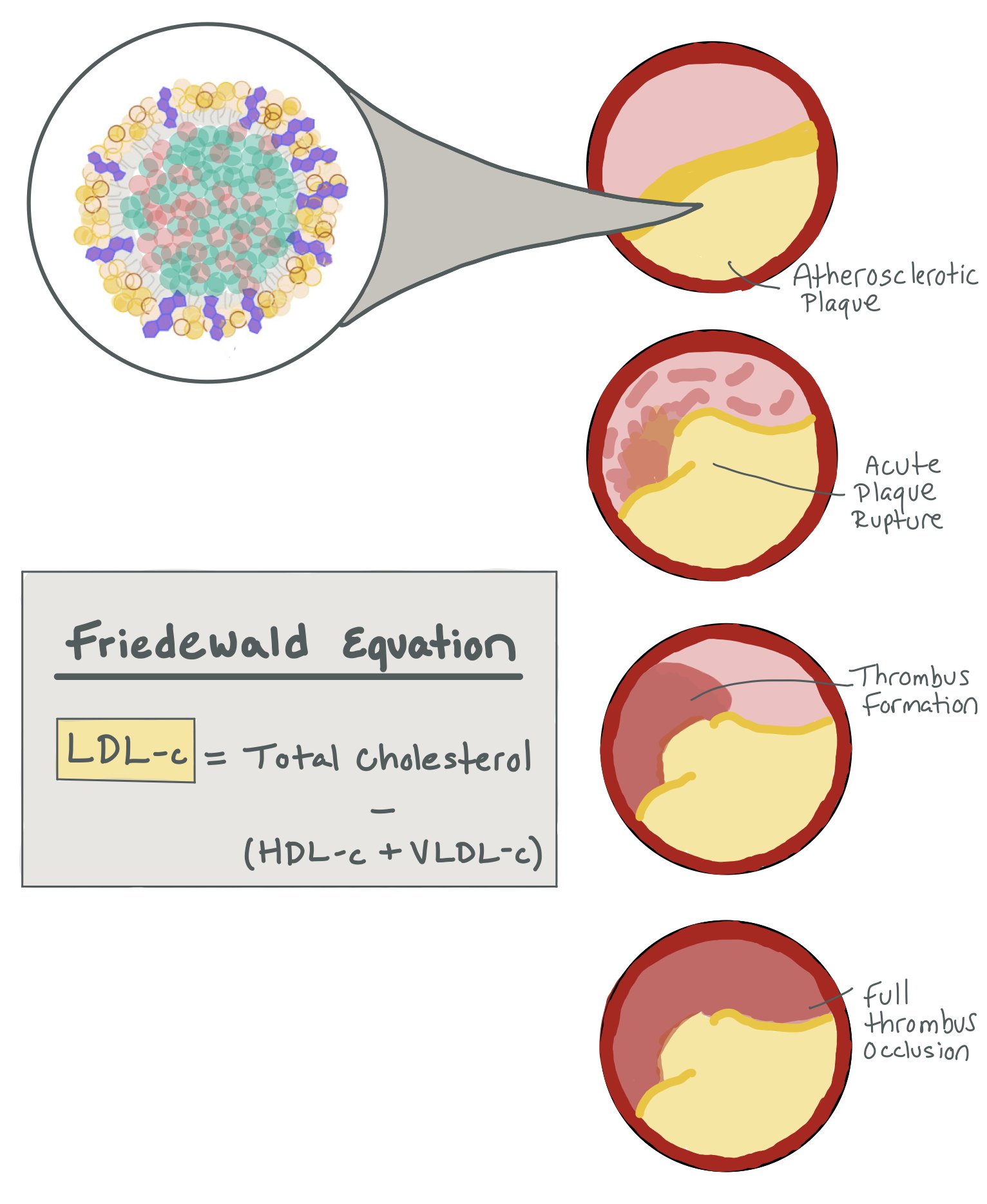

Measures total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-c, i.e. “good cholesterol”), and triglycerides. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (aka LDL-c) is a measured value based on these measurements (see figure). As LDL-c is the dominant form of atherogenic cholesterol, we use this value to help guide our management of patients with elevated cholesterol.

Two additional labs:

Lp (a): lipoprotein (a) is a modifiable form of LDL-c that appears to possess atherogenic potential

Apo (B): the major apolipoprotein embedded in LDL-c and VLDL with elevated levels correlating to higher ASCVD risk.

Prior to collecting a lipid panel, it is important patients fast 10 to 12 hours. However, fasting has been shown to only have slight, clinically insignificant effects on total cholesterol, HDL-C and LDL-C. Since LDL-C is a calculated value, the number is more accurate when fasting. That said, if patients are high-risk (i.e. family history, age >40, etc), they should fast prior to getting their lipid panel drawn.

The Freidewald Equation is especially less accurate when LDL-C is <100 mg/dL, which is important in patients who are very high risk that we are trying to treat to goals of < 55 mg/dL. Notably, it is also less accurate in patients with metabolic syndrome with triglyceride levels between 150-400. The Nation Lipid Association recommends using the Martin-Hopkins Equation to calculate LDL-C if LDL-C is < 100 or triglycerides are between 150-400.

The picture above shows how LDL-C is the dominant form of atherogenic cholesterol that ultimately clogs the arteries and can lead to acute plaque rupture. LDL-C is a calculated number that is calculated through the Friedewald Equation.

Additionally, you can consider ordering lipoprotein (a) or apoprotein B on high-risk patients or patients with elevated baseline total cholesterol or triglycerides to get more accurate risk assessments.

Similarly, lipoprotein(a) levels do not change in response to normal food intake with lipoprotein(a) having been established as an independent risk factor for MI and ischemic heart disease. Fasting is necessary in the collection of triglycerides, however, in that food can raise triglycerides levels to a modest degree, especially after a high fat meal.

Lipoprotein(a) is mostly genetically determined and does not vary significantly throughout a person’s life. Although PCSK9i have been shown to reduce by ~25-30%, emerging therapies such as Pelacarsen reduce by ~2/3 but are not yet commercially available.

Calculating non-HDL-C (or getting apo(B) as already mentioned) may be reliable if LDL-C <100, triglycerides are elevated, or the patient is not fasting. It should be noted that when converting between LDL-C and non-HDL-C, the non-HDL-C goal should be ~30 mg/dL higher.

The picture above shows how the chylomicron breaks down into the LDL and Lp(a) particles. You can also see the apo(a) on the Lp(a) particle.

There are many risk factors that affect the prevalence of and mortality from CVD. For instance, men have a higher overall prevalence of and mortality from CVD; however, women experience higher mortality from certain cardiovascular events, such as stroke. The prevalence of CVD also differs by race and ethnicity with Black adults having the highest prevalence of CVD.

Primary vs. Secondary Prevention

Primary Prevention:

According to the American College of Cardiology, risk assessment for primary prevention should occur at least every 4 to 5 years starting at age 20. Primary prevention seeks to prevent events from atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD).

ASCVD is a subset of CVD caused by atherosclerosis, including coronary heart disease, stroke, and peripheral artery disease. Modifiable risk factors account for 50 to 70% of CVD events and mortality globally. It is important to note there are specific patient populations at increased risk for ASCVD events, in which risk estimations and pooled cohort equations underestimate associated risk. Patients with HIV, chronic inflammatory disorders, a history of preeclampsia, pregnancy-induced hypertension, polycystic ovarian syndrome, and gestation diabetes are often at a higher risk than predicted by pooled cohort equations and calculators.

Secondary Prevention:

Patients with established ASCVD have an elevated risk of subsequent events, including MI, stroke, and death. Patients with ASCVD include those who have had a cardiovascular event such as MI, stroke, TIA, or display symptomatic presentations such as angina or limb claudication.

Imaging evidence of atherosclerosis, such as CT coronary angiogram, calcium score test, or other imaging documenting ≥50% atherosclerosis in the coronary, cerebrovascular, or peripheral arterial beds, may highlight the need to treat a patient more aggressively.

The 2018 AHA/ACC guidelines on cholesterol management divide patients with ASCVD into high-risk and very high-risk categories. Very high-risk is considered those patients with a history of multiple ASCVD events or 1 major ASCVD event and multiple high-risk conditions such as age ≥ 65 years, diabetes, hypertension, current smoking, CKD (eGFR 15-59 mL/min/1.73 m2) among others. In high-risk patients, use a maximally tolerated statin to lower LDL-C levels by ≥50%. Meanwhile, in very high-risk ASCVD, it is reasonable to add a non-statin lipid lower agent to maximally tolerated statin therapy when the LDL-C level remains ≥70 mg/dL (≥1.8 mmol/L). In patients at very high risk whose LDL-C level remains ≥70 mg/dL (≥1.8 mmol/L) on maximally tolerated statin and ezetimibe therapy, adding a PCSK9 inhibitor is reasonable. For patients with ASCVD, lifestyle modifications and adjunctive drug therapies demonstrate proven benefit.

ASCVD vs PREVENT Risk Calculators

In 2023, AHA introduced a new cardiovascular risk calculator, PREVENT (Predicting Risk of cardiovascular disease EVENTs). This calculator differs from the previous risk screening tool in that ASCVD included variables of age, sex, race, blood pressure, total and HDL cholesterol, and histories of smoking, diabetes, and treatment for hypertension, whereas PREVENT includes additional variables of body-mass index, estimated glomerular filtration rate, and (optionally) glycosylated hemoglobin and urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio, omits race, and provides the option of including a patient’s zip code.

PREVENT provides more extensive output, including both 10-year risks for people who are aged 30 to 79 and 30-year risks for people who are 30 to 59 years old.

Lifestyle Modifications

Lifestyle Modification

In 2022, the American Heart Association developed “Life’s Essential 8,” which include multiple elements to help improve and maintain our patient’s heart health. This checklist focuses on health behaviors and health factors:

1. Diet — It is important to obtain a dietary history in patients with high ԼDL-С to identify specific dietary patterns that can raise ԼDԼ-С (e.g., ketogenic or paleolithic diets). If the patient is on such a ԁiet, we recommend lifestyle changes, remeasure ԼDL-C, and then treat with pharmacotherapy as necessary to further reduce LDԼ-С. Heart-healthy diets emphasize vegetables, fruits, legumes, whole grains, and fish and minimize processed meats, refined carbohydrates, and sweetened beverages.

2. Increase Baseline Activity — Physical activity: Adults should engage in 150 minutes of moderate-intensity or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity per week. It is important to decrease sedentary behavior.

3. Smoking Cessation — Smoking cessation: It is important to emphasize that smoking is a major modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and its detrimental effects extend beyond just increasing cholesterol levels. Smoking contributes to both atherosclerosis and worsened lipid profiles

4. Healthy Sleep — Adequate sleep: The AHA recommends 7-9 hours of sleep per night for optimal heart health. Improving sleep hygiene (e.g., avoiding stimulants like caffeine and reducing screen time before bed) can have a positive effect on lipid profiles.

5. Weight Management — Weight loss: Counseling and comprehensive interventions such as calorie restriction are recommended. Losing as little as 5-10% of body weight can have significant benefits for lipid levels and overall cardiovascular health.

6. Cholesterol Management — Dyslipidemia management: For individuals with clinical atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) (such as a history of heart attack, stroke, or peripheral artery disease), LDL-C goal is <70 mg/dL in LDL-C from baseline, while those at risk their goal is LDL-C <100 mg/dL (although specific guidelines depend on the particular patient).

7. Blood Sugar Management — Hyperglycemia management: High blood sugar, especially in diabetes and pre-diabetes, can lead to dyslipidemia. Managing blood sugar through diet, exercise, and medications (e.g. metformin, SGLT2 inhibitors, and GLP-1) can help improve lipid profiles.

8. Blood Pressure Management — Hypertensive management: Medications like ACE inhibitors, ARBs, or beta-blockers are commonly used to manage blood pressure, which in turn can help in stabilizing lipid profiles. It’s essential to keep blood pressure well-controlled (preferably <130/80 mmHg) to reduce the risk of heart disease.

Social determinants of health (SDOH) should inform optimal implementation of treatment recommendations in primary prevention. AHA/ACC provide example considerations for addressing SDOH to prevent ASCVD events in the domains of diet, exercise and physical activity, weight loss, and tobacco treatment.

Medication Management: STATINS

When considering medication management in patients with elevated risk, there are many medication classes to choose. In most cases, statins are our first-line therapy, while Ezetimibe may be added to patients on maximum statin therapy who need additional lipid lowering. Bile acid sequestrants and PCSK9 inhibitors can also be used in resistant cases or in patients who cannot tolerate statin therapy.

Statin Therapy

Statins serve as the mainstay of lipid management and are crucial in the reduction of ASCVD risk. Statins are competitive inhibitors of HMG-CoA reductase, which serves as a rate limiting step in cholesterol biosynthesis in the liver. See the “Statin Classification by Expected LDL-C Reduction” from the 2018 ACC/AHA Cholesterol Management Guidelines.

In primary prevention, recommendations for ѕtаtiո therapy are based upon the LDԼ-C level and baseline CVD risk:

LDL-C ≥190: For all patients with LDL-C ≥190 mg/dL, treat with a high-intensity statin based on elevated LDL-C alone.

For patients with LDL-C < 190 and who do not have diabetes, initiation and intensity of statin therapy is guided by patient’s 10-year estimated CVD risk:

LDL-C <190 and Intermediate (7.5 to 20%) or High (≥ 20%) 10-year CVD Risk: For those patients with intermediate or high 10-year ASCVD risk, typically treated with a moderate-intensity statin. However, it is reasonable to start with a high-intensity statin in those patients with a high 10-year CVD risk.

LDL-C <190 and Borderline (5 to 7.4%) 10-year CVD Risk: In patients with LDL-C < 190 and borderline risk of a 10-year ASCVD event, shared decision-making is made on the part of you and the patient. In this patient population, we consider additional factors and evaluate individualized patient-centered care to guide decisions such as patient history like comorbidities and family history and risk stratification with coronary artery calcium (CAC) scoring. Risk-benefit conversations are especially important in this patient group.

LDL-C > 160 and Borderline (5 to 7.4%) 10-year CVD Risk: initiate statin therapy

<190 and Low (<5%) 10-year CVD Risk: For most patients with LDL-C <190 and 10-year risk <5%, we do not start statin therapy.

In secondary prevention, ASCVD is recommended to be reduced with a high-intensity statin or maximally tolerated statin. In patients with ASCVD at very high-risk, additional nonstatin therapies should be considered (Nonstatin therapies are discussed below).

Side effects can vary somewhat among the different statins; however, class-wide effects include the development of muscle symptoms and increased risk of new-onset diabetes. It is essential to assess adherence as nonadherence can contribute to lack of achieving appropriate LDL-C reduction.

*** Coronary CT angiography (CCTA) may be helpful for a subset of symptomatic patients in which presence and extent of CAD may alter medical or interventional management.

SAMSON Trial: Howard, et al. enrolled participants on statin therapy with side effects sufficiently severe enough to result in complete nonadherence to assess symptom scores after reinitiating therapy. In this trial, participants received 12 1-month medication bottles, 4 containing atorvastatin 20 mg, 4 placebo, and 4 empty. Mean symptom score was higher in statin months (16.3; 95% CI: 13.0-19.6; P < 0.001), but also in placebo months (15.4; 95% CI: 12.1-18.7; P < 0.001), with no difference between the 2 (P ¼ 0.388). Study investigators concluded side effects from taking statin tablets are verifiable but are driven by the act of taking tablets rather than whether the tablets contain a statin.

Repeat Lipid Panel

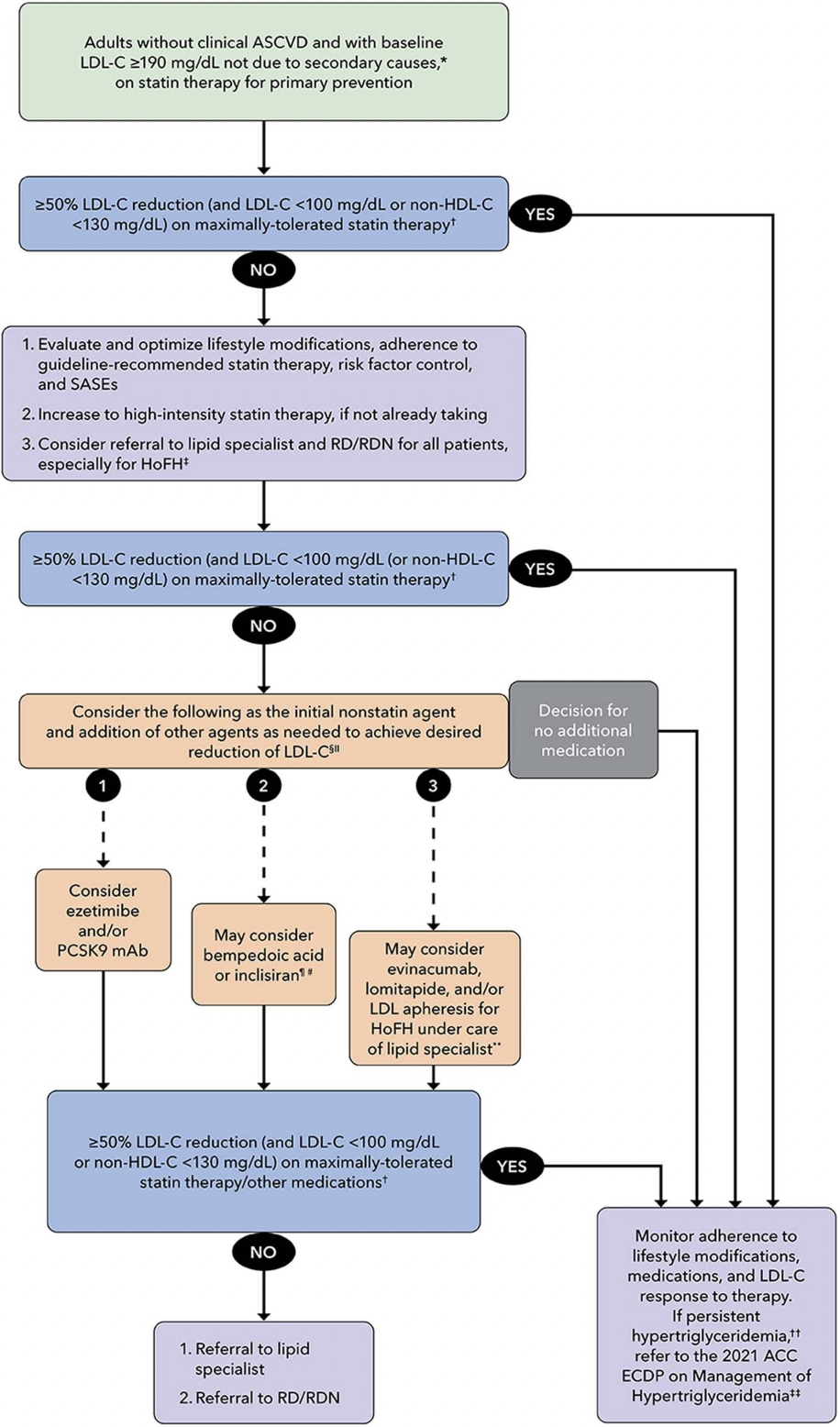

Labs should be measured 4 to 6 weeks after initiating statin therapy. If a patient on a high-intensity statin does not see a ≥50% LDL-C reduction (and LDL-C <100 or non-HDL-C <130 in certain primary prevention patients in borderline or intermediate categories), it is important to optimize lifestyle modifications and assess adherence. In patients who do not attain target LDL-C reduction, referral to a lipid specialist and registered dietician is appropriate. In the event a patient is still unable to see a ≥50% LDL-C reduction (and LDL-C <100 or non-HDL-C <130) on maximally tolerated high-intensity statin therapy, non-statin therapies may then be considered.

Goals

The 2022 ACC Expert Consensus regards ≥50% LDL-C reduction for high-intensity statin therapy doses and 30% to 49% reduction for moderate-intensity doses as indicators for efficacy. For primary prevention, the general target for LDL-C is ≤ 100 mg/dL, while for secondary prevention the general target is LDL-C ≤ 70 mg/dL.

Meanwhile, for secondary prevention, target for LDL-C is ≤ 70 mg/dL. An LDL-C threshold of 70 mg/dL in very high-risk patients serves as clinical consideration point to add non-statin therapies. For individuals at very high risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), the current target for LDL-C (low-density lipoprotein cholesterol) is to achieve levels below 55 mg/dL, especially following any ACS event when LDL was already < 70 mg/dL.

Medication Management: Non-STATINs

Subsequent management

In primary prevention, indications for pharmacotherapy outside statins include patients who are statin intolerant, those unwilling to start statins because of side effects, for patients at intermediate or high risk of CVD events who do not achieve adequate LDL-C lowering on statin monotherapy. The 2018 AHA/ACC cholesterol guideline recommends use of an LDL-C threshold of ≥100 mg/dL (1.8 mmol/L) to consider the addition of non-statin therapy to maximally tolerated statin therapy in patients who still have LDL-c >70 mg/dL or >55 mg/dL in very high risk populations.

Ezetimibe will reduce LDL-C by approximately 20-25%. Ezetimibe is an antilipemic agent that inhibits the absorption of cholesterol at the border of the small intestines via NPC1L1. Ezetimibe is recommended as an initial non-statin therapy in patients with clinical ASCVD who are receiving maximally tolerated statin therapy and have an LDL-C level ≥70 mg/dL.

PCSK9 inhibitors (like alirocumab (Praluent) and evolocumab (Repatha)) have been approved for primary prevention only in patients with baseline LDL >190 mg/dL and a family history of severe hypercholesterolemia. PCSK9 inhibitors can be used as an initial non-statin therapy in patients with clinical ASCVD; however, it is important to note that many insurance companies require ezetimibe trial prior to PCSK9 inhibitor approval.

Bempedoic acid will reduce LDL-C by approximately 20-25%. Bempedoic acid is an adenosine triphosphate-citrate lyase (ACL) inhibitor. This medication has been shown to lower the risk of a composite of major adverse cardiovascular events and is frequently given as a combination pill with Ezetimibe (called Nexlizet) that lowerse the LDL-C by about 30%.

Colesevelam will reduce LDL-C by 15-20%. Colesevelam binds with bile acids in the intestine to form an insoluble complex that is eliminated in feces. This increased excretion of bile acids results in an increased oxidation of cholesterol to bile acid and a lowering of the serum cholesterol. A barrier to using it is that it requires 6 tablets daily.

This chart is from the 2018 AHA/ACC Cholesterol Management Guidelines.

Aspirin Use in ASCVD

Low-dose aspirin might be considered in select adults 40 to 79 years old who are at a higher ASCVD risk but not an increased bleeding risk. ACC recommends the consideration of aspirin 81 mg/day if 10-year ASCVD risk is ≥10% if benefit outweighs bleed risk after clinician-patient discussion.

For secondary prevention, aspirin 81-162mg/day indefinitely is recommended. DAPT, or dual antiplatelet therapy, is recommended in addition to aspirin after PCI. DAPT is discussed further separately. Caution prasugrel use in patients over 70 years of age.

Meanwhile, for patients receiving anticoagulation therapy, aspirin carries an increased risk of bleeding with little to no benefit in preventing ischemic events. It is important to assess anticoagulation therapy as compared to aspirin therapy in patients with ASCVD and concomitant disease.

Smoking Cessation

Treating smoking as a chronic disease recognizes the physical dependence and learned, rewarding behaviors that are detrimental to the patient. A three-step model is employed as a framework when encouraging patients to stop smoking: Ask-Advice-Connect (Ask all patients about tobacco use, advise patients who smoke to stop, offer all patients both pharmacotherapy and behavioral treatments). Alternative models include the Five A’s Approach, in which patients are 1.) Asked about tobacco use, 2.) Advised to quit, 3.) Assessed for readiness to quit, 4.) assisted with quitting if ready, and 5.) Arranged for follow-up.

When working with patients ready to quit, it is important to follow initial steps of setting a quit date, reinforcing benefits to quitting, developing a treatment plan, and addressing barriers to quitting.

Pharmacologic options are available to assist patients with discontinuing tobacco use. It is suggested that patients utilize varenicline, buprenorphine, or a combination of two nicotine replacement therapies such as a patch, gum, or lozenges. Behavioral counseling, or cognitive behavioral therapy, is also essential to assist patients in quitting and should serve as a supplement to pharmacotherapy options.

Nicotine gum and lozenges doses are dependent on a patient’s “time to first cigarette.” In patients in which time to first cigarette in the morning is less than 30 minutes after working, 4 mg is recommended for nicotine gum and lozenges. Meanwhile, for those patients in which time to first cigarette in the morning is greater than 30 minutes after working, 2 mg is recommended.

Back to the Case:

When thinking about lipid management, what considerations do you need to have? What resources should you be using when determining which therapies a patient should be treated with? What is a coronary CT scan and when should you consider getting this scan to help establish cardiovascular risk?

What is the patient’s current physical activity level? Does he exercise regularly? Would lifestyle modifications be suitable and realistic for this patient? As part of the management plan, exercise is a critical recommendation for improving cardiovascular health, weight management, and lipid profile. Given his overweight status and the stress of his sedentary job, starting with small, achievable goals may be more appropriate, such as short walks or light physical activities that don’t require significant time commitments.

While it is essential to encourage some form of physical activity, gradual implementation of exercise is important, recognizing that the patient might need support and motivation over time. Adjust expectations and offer practical strategies, such as breaking up exercise into manageable sessions (e.g., 10 to 15-minute walks throughout the day) or incorporating activity into daily tasks (e.g., taking the stairs, walking during lunch breaks). In addition, discussing any potential barriers, like fatigue or lack of motivation, will be key in finding solutions and increasing his chances of success.

This patient would also benefit from smoking cessation counseling and pharmacologic options. Patients can start on two forms of nicotine replacement therapy such as a nicotine patch and gum. It is important this patient has shared decision-making in his plan, receives supplemental behavioral counseling, and understands the importance of quitting.

While not applicable for this patient, coronary CT angiography or calcium scoring can be useful and can be considered in individuals with borderline intermediate risk of ASCVD to help guide treatment decisions.

Which medications or drug classes would you first consider initiating in this patient? How frequently should you be checking lipids? If you need to escalate or change the medication due to ineffectiveness or adverse drug reactions, which medications should you consider adding?

Given this patient falls into high-risk group within secondary prevention, it is recommended to initiate a high-intensity statin, such as atorvastatin 80 mg or rosuvastatin 40 mg. Labs should be measured 4 to 12 weeks after initiating statin therapy. Lipids can be checked every 3 to 12 months thereafter as needed per multi-society guidelines. It is important to offer additional counseling and education on lifestyle modifications and suggest gradual, incremental changes to diet and exercise.

The main adverse events related to statin therapy include muscle symptoms (rhabdomyolysis/myopathy) and new onset diabetes. While initiating a statin, it is important to monitor a patient’s lipid panel, hepatic transaminase levels, and CPK if signs of muscle pain. Counseling can include important lifestyle modifications in addition to pharmacotherapy, to avoid consumption of grapefruit juice, to avoid red yeast rice, and to notify us if pregnancy is planned or suspected in female patients.

When considering additional nonstatin therapies, guidelines recommend initiating ezetimibe or PCSK9 inhibitors—(like alirocumab (Praluent) and evolocumab (Repatha).

Does it matter if a patient was fasting prior to getting the lipid panel? If so, why does it matter? Can you use any information from that lab test? What if you also got a Lipoprotein (a) test?

Fasting can impact certain components of a lipid panel, particularly the triglycerides. Food intake can moderately increase labs associated with cholesterol and triglycerides. Per AHA/ACC guidelines, pharmacotherapy recommendations and dose adjustments are most often based on LDL-C; however lipoprotein(a) is clinically correlated to ASCVD risk and subsequent events.

If a patient has high triglycerides, should you treat them?

By definition, hypertriglyceridemia occurs when the TG level reaches ≥150; however, elevated triglyceride levels are not a target for therapy unless ≥500 with recommendations being to reduce levels to <500. AHA/ACC guidelines recommend first identifying and treating secondary factors of hypertriglyceridemia, such as diabetes, hypothyroidism, or drug-induced causes. For patients with elevated triglycerides >500, AHA/ACC recommend initiation or intensification of statin therapy. Icosapent ethyl can be considered if triglycerides are >150 mg/dL, the patient has diabetes, and a high risk of ASCVD or known ASCVD.

What is the role of aspirin in primary prevention of cardiovascular disease? When should we consider or discontinue this medication in our patients?

Low-dose aspirin might be considered in select adults 40 to 79 years old who are at a higher ASCVD risk but not an increased bleeding risk. ACC recommendations the consideration of aspirin 81 mg/day if 10-year ASCVD risk is ≥10% if benefit outweighs bleed risk after clinician-patient discussion.

For secondary prevention, aspirin 81-162mg/day indefinitely is recommended. DAPT, or dualantiplatelet therapy, is recommended in addition to aspirin after PCI. DAPT is discussed further separately.

For our 55-year-old patient, he would be a candidate for indefinite low-dose aspirin therapy following his MI. While not currently an issue in this patient, in the event he were to be started on anticoagulation therapy such as a DOAC, aspirin is recommended to be discontinued.

Further Learning:

Resident Responsibilities:

When assessing the risk of CVD events in patients, stratifying patients into risk categories guides pharmacotherapy decision-making strategies. AHA/ACC stratifies patients into low, borderline, intermediate, and high-risk categories. There are currently two risk calculators available to determine risk of cardiovascular events: ASCVD and PREVENT.

·For primary prevention, it is worthwhile looking at any non-gated CT chest imaging a patient may have in their chart to evaluate for coronary calcification and guide management (see picture with calcification).

Patient education, especially in outpatient settings, is critical. A key intervention is educating patients about modifiable risk factors and the importance of lifestyle changes, including diet, exercise, and smoking cessation. Adherence is key to observe the desired LDL-C reduction.

The risk of not adequately managing primary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) means increased likelihood of adverse cardiovascular outcomes. Patients are at an increased risk of cardiovascular events, progression of atherosclerosis, and higher mortality risk.

Additional Resources:

Landmark trials in LDL primary prevention:

For the approval of various statin medications: WOSCOPS (pravastatin), AFCAPS/TexCAPS (lovastatin), MEGA (pravastatin), ASCOT-LLA (atorvastatin), JUPITER (rosuvastatin)

REPRIEVE: Pitavastatin to Prevent Cardiovascular Disease in HIV Infection

Podcasts:

Cardionerds: Lipid Management with Drs. Ann Marie Navar & Nishant Shah (Episode 42)

The Curbsiders: Lipids Update and Cardiovascular Risk Reduction with Erin Michos MD (Episode 191)

Guidelines

2022 US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF): Final recommendation statement on statin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults

2020 World Health Organization (WHO): HEARTS – Technical package for cardiovascular disease management in primary health care: Risk-based CVD management

2019 ACC/AHA: Guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease

In the picture above, you can see the calcification within the arteries of this patient on the CT scan. Seeing this should clue you into the fact that this patient has significant atherosclerosis.

How’d we do?

The following individuals contributed to this topic: Daniel Schreiber, PharmD; Stephanie Dwyer Kaluza, PharmD, BCCP; Avi Aronov, MD,

Chapter Resources

Cheung AK, Kronenberg F. Lipid management in patients with nondialysis chronic kidney disease. UpToDate website. Updated January 2024. Accessed March 1, 2025. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/lipid-management-in-patients-with-nondialysis-chronic-kidney-disease?search=lipids+management+in+primary+prevention&source=search_result&selectedTitle=4%7E150&usage_type=default&display_rank=3

Pignone M, Cannon CP, et al. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol-lowering therapy in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. UpToDate website. Updated January 2024. Accessed March 1, 2025. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/low-density-lipoprotein-cholesterol-lowering-therapy-in-the-primary-prevention-of-cardiovascular-disease

Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(10):e177-e232. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2019.03.010.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Disease in Adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2025;333(8):789-795. doi:10.1001/jama.2025.0010.

Brett AS. A new cardiovascular risk calculator from the American Heart Association. NEJM Journal Watch.

Chrispin J, Martin SS, Hasan RK, Joshi PH, Minder CM, McEvoy JW, Kohli P, Johnson AE, Wang L, Blaha MJ, Blumenthal RS. Landmark lipid-lowering trials in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Clin Cardiol. 2013 Sep;36(9):516-23. doi: 10.1002/clc.22147. Epub 2013 May 30. PMID: 23722477; PMCID: PMC6649586.

Howard JP, Wood FA, Finegold JA, Nowbar AN, Thompson DM, Arnold AD, Rajkumar CA, Connolly S, Cegla J, Stride C, Sever P, Norton C, Thom SAM, Shun-Shin MJ, Francis DP. Side Effect Patterns in a Crossover Trial of Statin, Placebo, and No Treatment. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021 Sep 21;78(12):1210-1222. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.07.022. PMID: 34531021; PMCID: PMC8453640.

Writing Committee, Lloyd-Jones DM, Morris PB, et al. 2022 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on the Role of Nonstatin Therapies for LDL-Cholesterol Lowering in the Management of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Risk: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee [published correction appears in J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023 Jan 3;81(1):104. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.11.016.]. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;80(14):1366-1418. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2022.07.006

Nordestgaard BG, Langsted A, Mora S, et al. Fasting is not routinely required for determination of a lipid profile: clinical and laboratory implications including flagging at desirable concentration cut-points-a joint consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society and European Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(25):1944-1958. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehw152

Jones R, Arps K, Davis DM, Blumenthal RS, Martin SS. Clinician guide to the ABCs of primary and secondary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 Mar 30. Available from: https://www.acc.org/Latest-in-Cardiology/Articles/2018/03/30/18/34/Clinician-Guide-to-the-ABCs